Our Founding Fathers

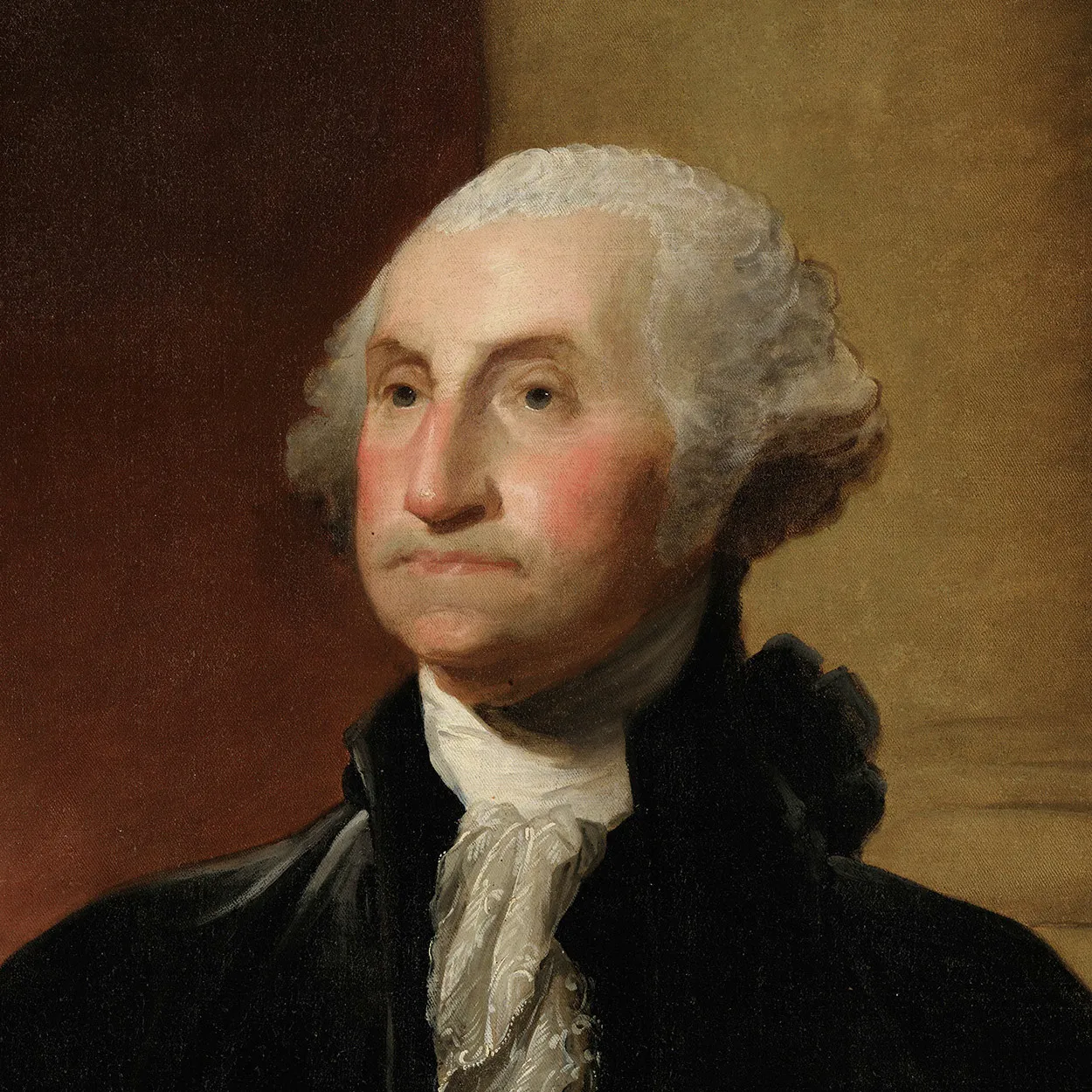

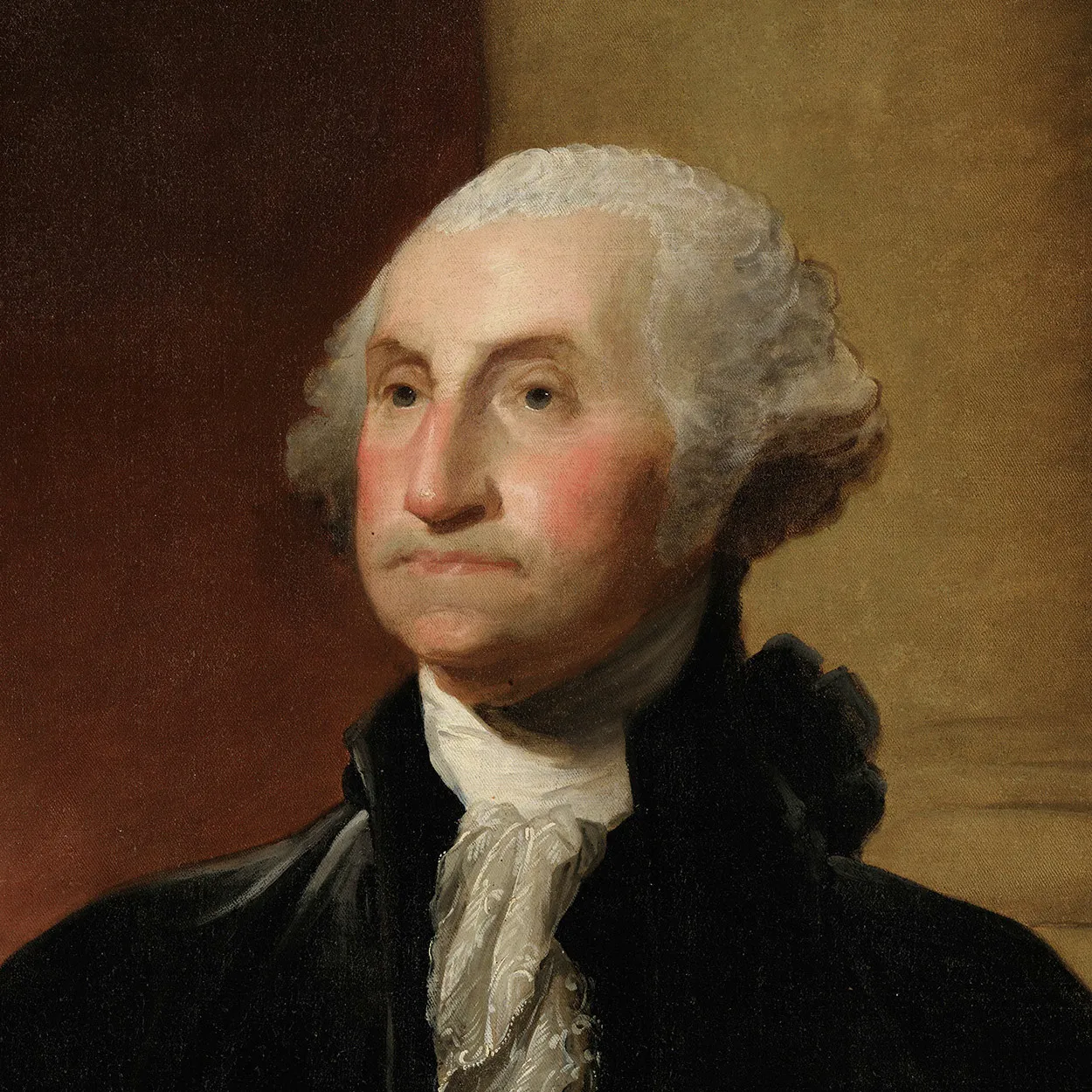

George Washington

America’s First President

Surveyor turned statesman, George Washington stands towering among his contemporaries as a pillar of resolve and leadership. His courage amid Revolutionary turmoil and his wisdom in governance secured his legacy as the father of the country.

Early Life

Born February 22, 1732, George Washington was the eldest child of Augustine and Mary Ball Washington’s six children, with his widowed father having two sons from a previous marriage.

His father was a modestly wealthy planter and justice of the county court owning several properties throughout Virginia, including their Popes Creek plantation where George was born.

When George was just 11 years old, his father unexpectedly passed and drastically shifted George’s trajectory. Unlike his brothers, he didn’t receive a formal education in England, making him one of the few founding fathers who did not have a formal education or college degree.

However, he was not uneducated. Through private tutors and some local schooling, George studied reading, writing, manners, and to become a surveyor, had a special focus in trigonometry and geometry.

Early Career

Throughout his young adulthood, he trained and worked as a surveyor, but this would be short-lived, when he felt called to a higher purpose. Following in the footsteps of his late, older brother Lawrence, George sought a military commission from Virginia Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie.

In October 1753, 21-year-old Major Washington was ordered to the Ohio River Valley to make peace with the Iroquois Confederacy and demand the French leave claimed British territory. The French refused.

Promoted to lieutenant colonel in February 1754, Washington led 150 men to Ohio where they killed 10 Frenchmen, including Commander Joseph Coulon de Villiers, Sieur de Jumonville.

To recover from their engagements, they set up Fort Necessity – a poorly placed and makeshift fort. They were soon overwhelmed and Washington was forced to surrender a humiliating defeat, and due to translation issues, mistakenly admitted to the assassination of Commander Jumonville. This event led to the start of the French and Indian War.

After, Washington declined a captain’s position – a demotion – of one of the newly formed regiments because British orders stated that a colonial could not be ranked any higher.

Instead, he served as an aide to General Edward Braddock and in battle had two horses shot from under him and four shots through his coat. Later in the war, he became a brevet brigadier general. Never receiving a royal commission would mark the start of his resentment against the British.

A Return to Civilian Life

After the war, Washington returned to Mount Vernon to manage the property, and married a widow, Martha Dandridge Custis. He also won a position in the Virginia House of Burgesses after losing his first race.

While they enjoyed maintaining the property, Washington couldn’t ignore the blatant overreach by the English government. They were loyal British subjects, but aggravated by the fact that they had no representation in parliament.

As a western territory land speculator, Washington was particularly impacted by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which banned settlement in the region. Not to mention, he fought a war to expel the French from this territory that he himself was now barred from.

During this period, Parliament also passed the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1766 and 1767, the Intolerable Acts of 1774.

While many of the acts were repealed, the disapproval of the colonists would only grow.

American Revolution

On April 19, 1775, “The shot heard round the world” at the Battles of Lexington and Concord proved to be the point of no return.

Washington hesitantly accepted his appointment to Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army on June 15, 1775.

General Washington’s Army lacked supplies, training, and cohesion, while the British military represented the world’s foremost fighting force. Failure meant not merely defeat but condemnation as a traitor to the Crown, punishable by death.

Washington’s early success at the Siege of Boston was overshadowed by losses in New York. Forced to retreat across New Jersey after losing key territories, Washington saw his army dwindle due to desertions and low morale.

The Revolution hung by a thread, but his bold crossing of the Delaware River on Christmas night in 1776 led to the surprise victory at Trenton, a turning point that reignited the American cause.

The next challenge was the brutal winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge. Disease and starvation ravaged the camp, but time and training transformed the army into a disciplined fighting force.

Despite setbacks at Brandywine and Germantown, the ultimate victory came at Yorktown in 1781, when Washington trapped General Cornwallis, forcing his surrender.

As an act of good faith, General Washington went before Congress to surrender his commission as commander-in-chief. The war was complete.

The Articles of Confederation

After six years of fighting and devastation, the conclusion of the war in 1783 brought an uneasy peace. They may have won the war, but governing the new nation proved more difficult.

Washington and others quickly realized the fragility of the new nation under the Articles of Confederation. A fragility validated during Shays’ Rebellion in 1786-87, an armed, farmer uprising when the federal government couldn’t adequately respond.

In a letter to James Madison in 1787, Washington wrote that the nation was at risk of “anarchy and confusion.” His participation in the Constitutional Convention was pivotal, lending credibility to the effort of drafting a more robust government.

The Presidency

Called for service by unanimous vote of the Electoral College, President Washington humbly took office on April 30, 1789, in New York City.

He set critical precedents that shaped the presidency. Notably, the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the federal judiciary system. In foreign affairs, he navigated the French Revolution, maintaining neutrality despite public outcry, and opposition from his own cabinet.

In 1794, during the Whiskey Rebellion, farmers protested against a federal excise tax. Washington personally led 13,000 militiamen to Pennsylvania to quell the revolt, marking the first real test of federal authority under the Constitution.

Washington’s most defining act was his voluntary departure from office after two terms. In his Farewell Address in 1796, he warned against political factions and foreign entanglements, embodying his belief in the long-term welfare of the nation. His words, “after forty-five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be to the mansions of rest.”

Retirement

Washington’s return to Mount Vernon in March 1797 long-awaited, but short-lived. He passed on December 14, 1799, marking the end of an era. The grief that swept the nation affirmed his legacy as the “father of his country.”

In 1976, during the nation’s bicentennial celebration, he was posthumously honored as General of the Armies. A grade that declared him as the highest ranking military official past or present in perpetuity.

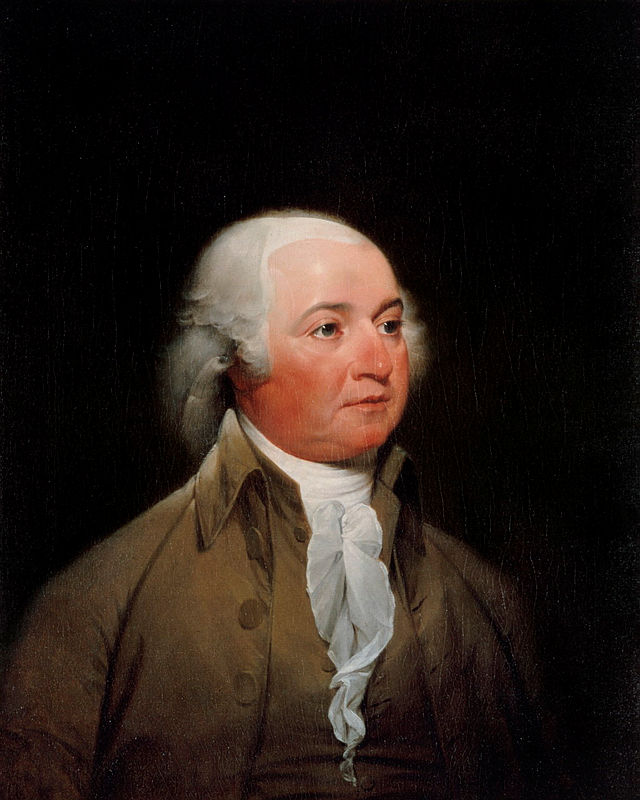

John Adams

America’s Second President

A fiery pen and an unshakable conscience, John Adams stood at the nation’s birth as its moral spine—unyielding in principle, tireless in purpose. He championed independence before it was safe, and government before it was popular. Though rarely adored in his time, Adams gave the republic what it needed most: honesty, structure, and the rule of law.

Early Life

Born October 30, 1735, in Braintree, Massachusetts, John Adams was the eldest son of a modest farmer and shoemaker, Deacon John Adams, and Susanna Boylston. A descendant of Puritan settlers, Adams inherited their stern ethic and restless mind.

He entered Harvard College at fifteen, graduating in 1755, and soon turned to law—a profession where logic, language, and moral clarity converged. As a young attorney, he saw the colonies’ grievances mount, yet believed reform could be achieved within the empire.

That hope would not survive the decade.

Before the Revolution

In 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act. Adams, then 30, responded with a formal essay—A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law—warning against tyranny and defending the rights of Englishmen. His writing rang across New England, sharpening his reputation as both scholar and dissenter.

Despite growing unrest, Adams remained faithful to law. When British soldiers fired on civilians in the 1770 Boston Massacre, he took the unpopular step of defending them in court. “Facts are stubborn things,” he told the jury—and won acquittals for most of the accused. For Adams, justice was not partisan, and principle did not yield to popularity.

In 1774, he joined the First Continental Congress. By 1776, his pen and voice had made him one of independence’s fiercest advocates. He nominated George Washington to command the Continental Army, shaped policy from committee chambers, and became, in Jefferson’s words, “the colossus of independence” in the Second Continental Congress.

Declaration and Diplomacy

Though Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence, it was Adams who defended it—line by line, hour by hour, against skeptics and delay. He signed it not as a symbolic gesture, but as a direct defiance of the Crown, risking his life and family for the cause.

In 1779, Adams was sent abroad to secure vital alliances and funds. He negotiated loans with the Dutch and later joined Franklin and Jay in Paris to draft the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the war. He was direct and unpolished, but his resolve yielded dividends—his diplomacy secured favorable terms that affirmed U.S. sovereignty and expanded its western border to the Mississippi.

The Constitution and the Idea of Government

Though not present at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Adams helped lay its intellectual groundwork. In his political writings—particularly Thoughts on Government (1776) and A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America (1787)—he argued for a strong, balanced government with separated powers, independent courts, and a bicameral legislature.

He warned against unchecked democracy and unchecked aristocracy alike. “Power must be opposed to power,” he wrote, echoing the philosophy of checks and balances that Madison and others would enshrine in the Constitution.

His belief in virtue, restraint, and institutional design influenced not only the national charter but also the constitutions of several states.

Vice Presidency

Elected Vice President in 1789, Adams became the first to hold what he famously called “the most insignificant office ever the invention of man contrived.” Though the role offered little executive power, Adams treated it seriously—presiding over the Senate with rigor and setting lasting precedents in both behavior and procedure.

He broke at least 31 tie votes during his two terms, more than any Vice President since. He often sided with Federalists on questions of federal authority, debt assumption, and judicial structure. His votes helped solidify the powers of the new government—sometimes clashing with anti-Federalist senators who feared federal overreach.

Adams avoided participating in Senate debate, respecting the office’s neutrality, and rarely traveled or gave speeches, establishing the vice presidency as a constitutional fixture, not a political accessory.

His letters during this time reflect his quiet frustration with the ceremonial nature of the job—but also his belief that a stable republic required dignity and restraint at every level.

The Presidency

In 1796, Adams succeeded Washington as the second President of the United States—the first peaceful transfer of executive power in the new republic. He defeated his former ally Thomas Jefferson in a bitterly partisan election that revealed growing fractures between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans.

Adams’s presidency was defined by rising tensions with France. The Jay Treaty had enraged French leaders, who began attacking American ships. In response, Adams strengthened the navy, creating the Department of the Navy in 1798, and prepared for war. When France demanded bribes in what became known as the XYZ Affair, the American public was outraged.

Though calls for war thundered from Congress, Adams resisted. He sent envoys back to France and ultimately secured peace through the Convention of 1800. The move split the Federalist Party and cost him reelection—but preserved the fragile republic.

During this period, Adams approved the Alien and Sedition Acts—laws that sought to strengthen national security during a moment of real threats. Adams viewed them as protective and necessary for the stability of the country.

Losing to Jefferson in the election of 1800, Adams left office in 1801 with dignity, respecting the peaceful transfer of power—setting a critical precedent in a young democracy.

Retirement and Legacy

Adams retired to his farm in Quincy, Massachusetts. For the next 25 years, he wrote voluminously—letters, reflections, and memories. His correspondence with Thomas Jefferson—renewed after years of silence—became one of the most profound dialogues in American history, exploring everything from liberty and revolution to faith, aging, and memory.

He lived to see his son, John Quincy Adams, become the sixth President of the United States—an achievement he viewed with pride, but also with the wisdom of a man who knew power’s cost.

He once wrote that “posterity will never know how much it cost the present generation to preserve your freedom.” But in every court, every peaceful transition, every restraint of power by principle, the cost he bore—and the republic he helped frame—endures.

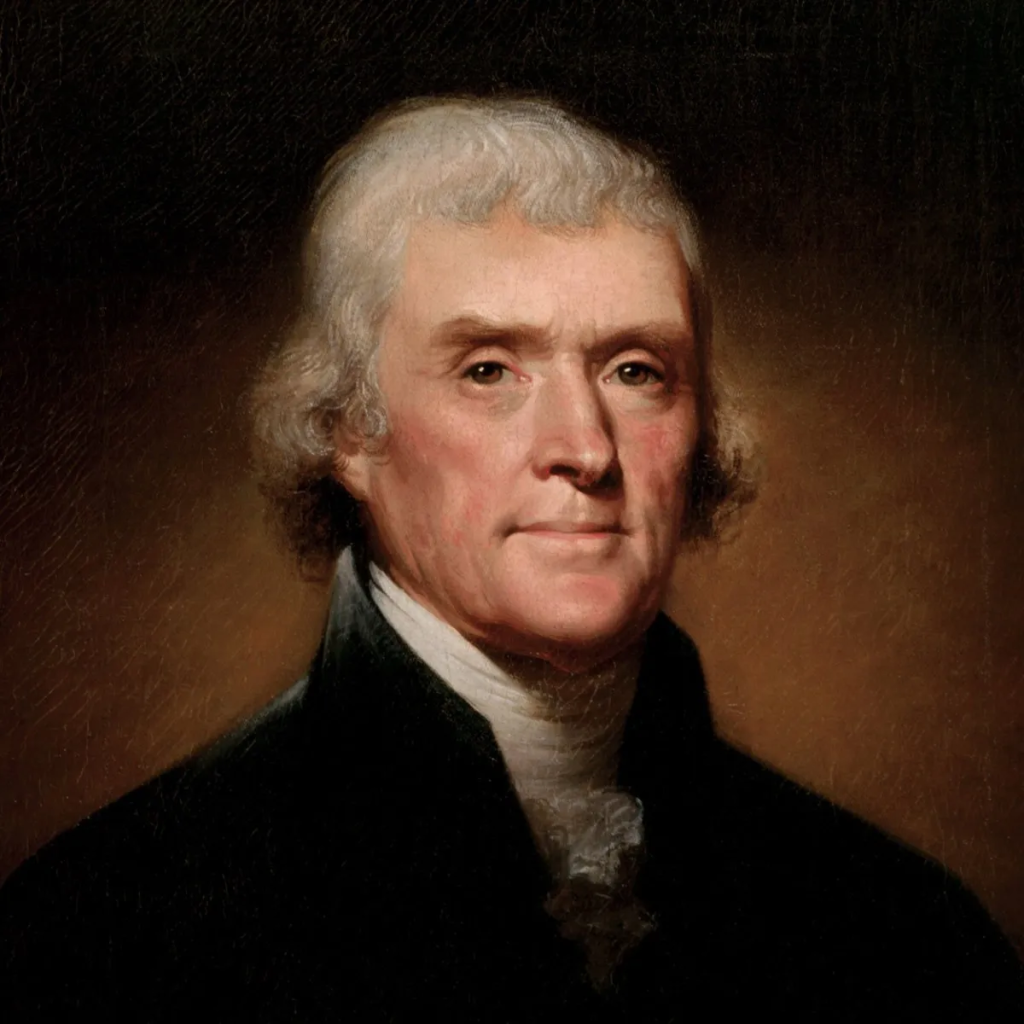

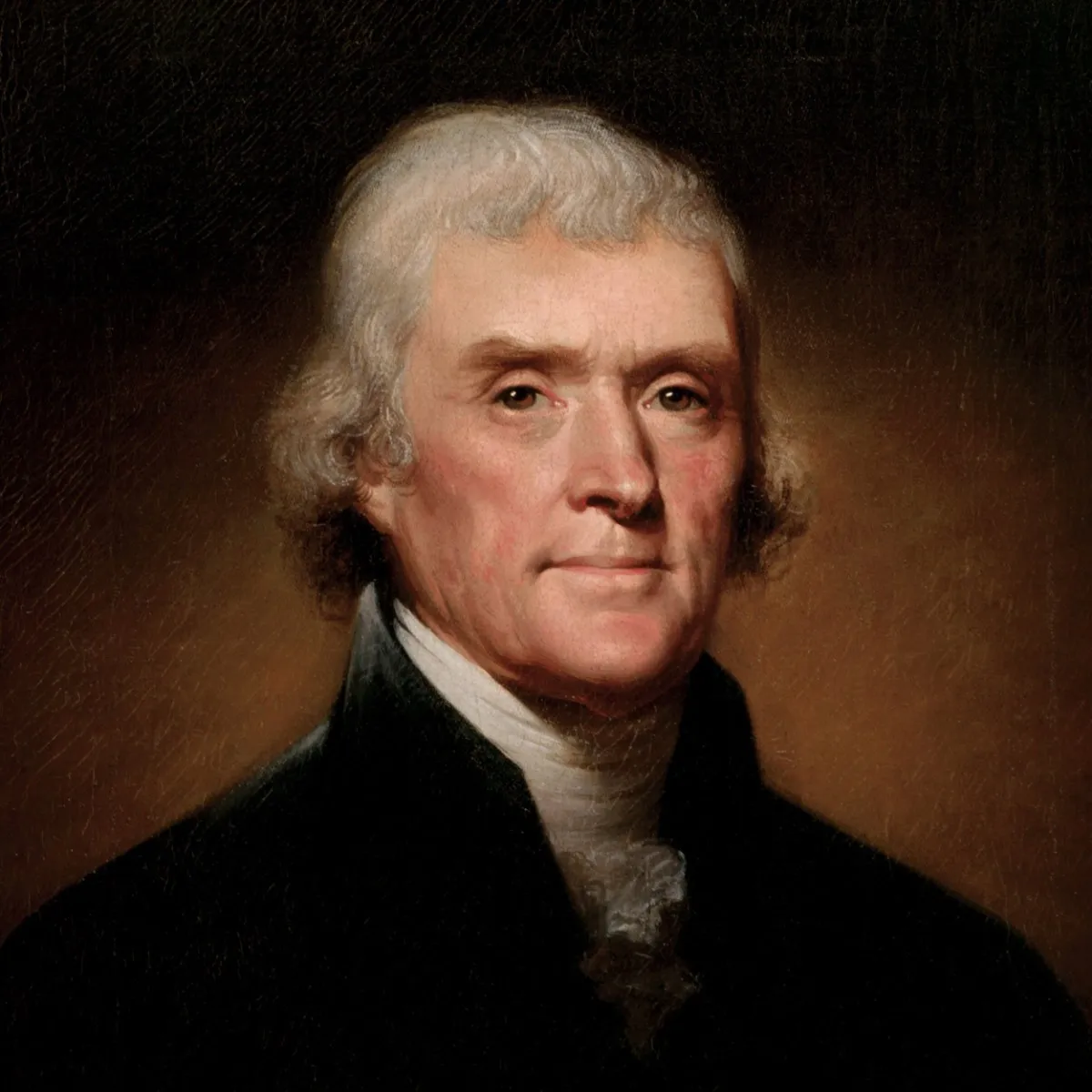

Thomas Jefferson

America’s Third President

A sage of liberty and architect of a nation, Thomas Jefferson fused Enlightenment ideals with steadfast resolve to shape a rising nation. His pen birthed its creed, his vision its expanse, securing his legacy as a cornerstone of the republic’s foundation.

Early Life

Born April 13, 1743, at Shadwell in Albemarle County, Virginia, Thomas Jefferson was the third of ten children to Peter Jefferson, a planter and surveyor, and Jane Randolph, from a respected Virginia family.

His father’s death in 1757, when Jefferson was 14, left him 5,000 acres and a sense of purpose that guided his youth.

From this early responsibility grew a hunger for knowledge. He studied with tutors who taught him Latin, Greek, and French, then enrolled at the College of William & Mary in 1760 at age 16. There, William Small sparked his interest in science, and George Wythe mentored him in law.

Staying in Virginia instead of studying abroad, he pored over books on law, history, and nature. By 1767, he was practicing law, building a strong start.

Early Career

Jefferson’s early years mixed legal work with public service. As a lawyer, he handled land disputes and small cases, earning respect for his sharp mind.

In 1769, Jefferson took his seat in Virginia’s House of Burgesses. Though soft-spoken in person, his written words cut sharply—resolutions against the slave trade and protests against British tyranny revealed a mind already charting a course toward resistance.

By 1772, he had married Martha Wayles Skelton, a wealthy widow, and brought her to Monticello—his still-unfinished retreat nestled atop a mountain. There, Jefferson indulged his passions for agriculture, architecture, and experimentation.

Two years later, he published A Summary View of the Rights of British America, a fiery pamphlet asserting the colonies’ right to self-govern. The work traveled far and fast, cementing Jefferson’s place as a rising patriot voice.

American Revolution

When war erupted in 1775, Jefferson’s role grew critical. Joining the Second Continental Congress that year, he arrived as fighting flared at Lexington and Concord. For a year, the colonies battled England while hoping for peace. In July 1775, Congress sent the Olive Branch Petition to King George III, a humble appeal to fix grievances like taxes and trade rules while pledging loyalty. The king not only rejected it, he refused to receive it—instead branding them rebels and hardening their resolve.

By June 1776, with war raging, Congress turned to Jefferson, then 33, to write a bolder statement. In 17 days, he crafted the Declaration of Independence, a stark contrast to the petition’s pleas. It didn’t beg—it demanded, listing the king’s wrongs like unfair taxes and quartering troops, and declaring “all men are created equal.”

This was open defiance, a call to arms after a year of skirmishes. To England, it was treason, a hanging offense, shifting the fight from resistance to full independence.

Adopted July 4, 1776, it rallied the colonies, turning a scattered revolt into a united stand for a new nation—a historic pivot that changed everything.

As Virginia’s governor from 1779 to 1781, Jefferson faced British raids that burned towns and strained supplies. In 1781, he fled Richmond as troops approached, drawing flak from critics. Yet he kept the state afloat, showing grit under pressure.

Post-War Roles

After the war, Jefferson took on key tasks. In 1782, Martha died after childbirth, leaving him with daughters Patsy and Polly. Devastated, he vowed not to remarry and focused on work. In 1783, he joined the Confederation Congress, proposing a decimal currency—still in use—and shaping western land policies.

The 1783 Treaty of Paris, signed in September, ended the Revolutionary War, recognizing American independence and setting boundaries from the Atlantic to the Mississippi. Jefferson, in Congress then and later as a diplomat, played a vital role in its aftermath. He pushed to enforce the treaty’s terms, ensuring Britain vacated western forts and Americans paid pre-war debts—a tricky balance.

In 1785, as minister to France succeeding Franklin, he worked with John Adams and Franklin’s lingering influence to solidify these agreements, negotiating trade and fishing rights.

Staying until 1789, he admired France’s push for liberty but disliked the royal court’s excess, all while strengthening America’s global stance.

In 1787, when Shays’ Rebellion saw farmers in Massachusetts rise against taxes, Jefferson wrote positively from Paris, “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants,” seeing it as a healthy sign of vigilance.

Constitutional Convention

In France during the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Jefferson’s influence traveled through letters. He praised the Constitution’s design but feared it favored government over people. Urging Madison to add a Bill of Rights, he saw it pass in 1791—a victory for his principles.

Though absent, his ideas matched Washington’s push for unity and Hamilton’s call for structure, tempered by his faith in individual rights.

The Early Republic

Back in 1789, Jefferson became Washington’s Secretary of State. He sparred with Hamilton, who favored a strong central government. Jefferson backed states and farmers, founding the Democratic-Republican Party. Their clashes set the nation’s course.

In 1796, he narrowly lost the presidency but became Vice President under Adams in 1797 due to an election flaw. Opposing the Alien and Sedition Acts, which jailed critics, he wrote the 1798 Kentucky Resolutions, arguing states could defy unjust laws—a daring stand for freedom.

The Presidency

In 1800, Jefferson tied with Aaron Burr for president; Hamilton’s support broke the deadlock, and he took office in 1801. He shaped the presidency with a light touch, calling it a “Revolution of 1800.”

He cut army and navy budgets, axed a whiskey tax hated in the West, and trimmed the national debt by a third. He sent ships to fight Barbary pirates harassing American trade in the Mediterranean, showing strength abroad while keeping government lean at home.

Moving the capital to Washington, D.C., he set a modest tone, often greeting visitors in casual clothes.

In 1803, he bought the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon for $15 million, doubling America’s size. The Constitution didn’t explicitly allow this, and Jefferson, a champion of small government, wrestled with the decision. He’d long opposed federal overreach, yet saw this as a unique chance to secure the West against European powers. He pushed ahead, sending Lewis and Clark’s 1804–1806 expedition to explore it, mapping rivers and peaks.

In 1807, his embargo on trade with Britain and France, aiming to avoid the Napoleonic wars, misfired, hurting merchants and testing his leadership—a rare stumble.

Post-Presidency

Jefferson retired to Monticello in 1809, advising Madison and Monroe on wars and expansion. He wrote thousands of letters, defending a people-first government. In 1819, he founded the University of Virginia, designing its campus and curriculum; it opened in 1825, a crowning achievement.

In 1824, he and Adams, once foes, exchanged letters reflecting on their nation. Jefferson died July 4, 1826, at 83, on the Declaration’s 50th anniversary—the same day as Adams.

To the bitter end, John Adams’ last words were, “Thomas Jefferson survives,” not realizing his former Vice President had already passed.

Buried at Monticello, he listed the Declaration, religious freedom, and his university on his tombstone, omitting his presidency.

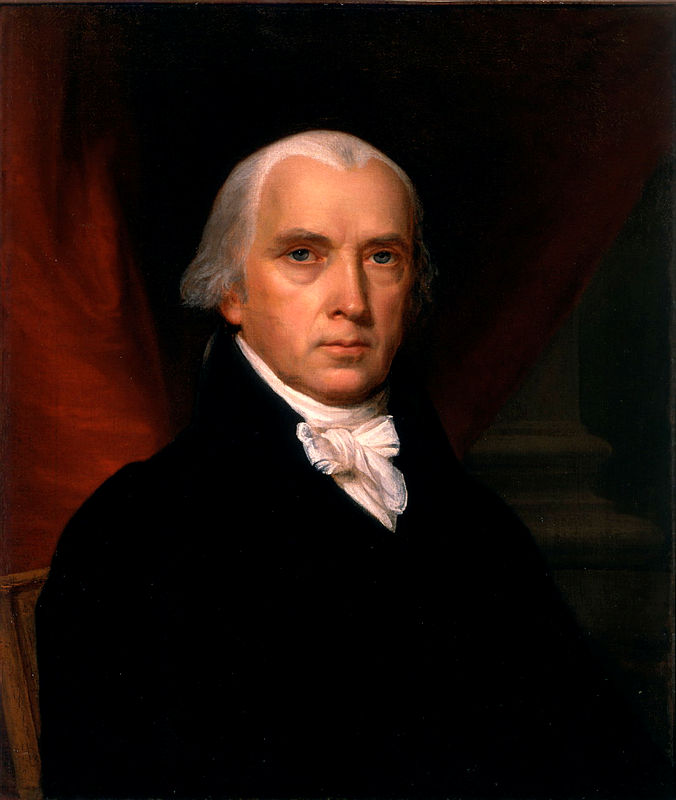

James Madison

America’s Fourth President

A steady mind behind revolutionary change, James Madison forged the American republic not through force, but through thought. He built the framework of its government, defended it in war, and guided it through crisis—leaving behind not speeches or spectacle, but a Constitution that endures.

Early Life

Born March 16, 1751, in Port Conway, Virginia, James Madison was the eldest son of a modestly wealthy planter, James Madison Sr., and Eleanor “Nelly” Conway. Raised on the family estate of Montpelier, he spent his youth not in physical pursuit—his health was often poor—but in the discipline of study.

Tutored in Latin, Greek, and mathematics, he devoured Enlightenment philosophy and ancient history with the quiet intensity that would define his life. At 18, he enrolled at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), completing a four-year curriculum in two. Rather than travel abroad like many of his peers, Madison returned home, steeped in classical thought and skeptical of unchecked power—prepared to build something new.

From Revolution to Reform

Though frail, Madison never sat idle during the Revolution. Elected to Virginia’s Convention in 1776, he helped draft the state constitution and pressed for religious liberty alongside Jefferson.

In 1780, he joined the Continental Congress, where he saw the fragility of a government built on goodwill alone. States quarreled, revenue faltered, and the war effort teetered on collapse. The Articles of Confederation had no teeth—no power to tax, no authority to unify.

By war’s end in 1783, Madison had grown convinced: independence meant little without order. The Revolution had birthed a nation; now it needed a government strong enough to hold it.

The Constitution

The tipping point came with Shays’ Rebellion in 1786—armed farmers in Massachusetts rising against debt and taxes. To Madison, it was no isolated riot but a symptom of systemic failure. That year, at the Annapolis Convention, he began pushing for a broader solution. The moment came in 1787, when delegates gathered in Philadelphia to reshape the republic.

Madison arrived with more than ideas—he brought a plan. In fact, he and the Virginia delegation arrived early to ensure they could set the agenda and tone for the entire proceedings.

His Virginia Plan proposed a national government grounded in popular representation, with three co-equal branches to check each other. He spoke softly but carried the room through logic, preparation, and patience. Though his proposals were revised in debate, his fingerprints remained on nearly every clause.

More than a framer, he was the Convention’s chronicler. His exhaustive notes remain the definitive record of the summer that reshaped the world.

And when the final draft was complete, it bore not only his design, but his voice. “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union…”—a phrase as radical as it was deliberate. Government, Madison believed, must begin with the people and be accountable to them alone.

But the Constitution still needed ratification—and opposition was fierce. Together with Hamilton and Jay, Madison penned The Federalist Papers, authoring 29 of the 85 essays. Federalist No. 10, perhaps his most famous, addressed the threat of faction, arguing that a large republic would better preserve liberty than a small one. Federalist No. 51 laid bare the logic of separation of powers: “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

With these essays, he didn’t just defend the Constitution—he gave it philosophy.

The Bill of Rights

Though initially skeptical that a list of rights was necessary, Madison recognized it was politically essential. As a congressman in the First Federal Congress, he drafted the amendments himself—drawing from state proposals and his own convictions. The result was the Bill of Rights: ten amendments enshrining freedom of speech, religion, press, due process, and more.

Even as the Constitution’s chief theorist, Madison was also its chief mechanic—turning abstract ideals into functioning governance. He drafted George Washington’s inaugural address to Congress in 1789, a message meant to set the tone for the new republic. Congress, moved by the President’s words and eager to respond, appointed a committee to craft a reply. The man they selected to write it? James Madison.

So Madison wrote back to himself, now as Congress. Washington then needed a second reply—and once again, Madison penned it. He spent the first weeks of government in quiet conversation with himself, embodying the new republic’s entire correspondence.

This small episode reflected a larger truth: Madison wasn’t just present—he was the connective tissue between ideas and institutions, giving voice to both.

In doing so, he didn’t just build the Constitution—he animated it.

The Presidency and the War of 1812

In 1809, Madison succeeded Jefferson as the fourth President of the United States. The early years of his presidency were marked by restraint—cutting the military, balancing the budget, and avoiding war. But British aggression on the seas—seizing American ships, impressing sailors, and arming Native resistance on the frontier—strained diplomacy past its limits.

On June 18, 1812, Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war against Britain. The vote was narrow. The war, unpopular. And within two years, British forces had marched into Washington and burned the Capitol and the White House. Madison and his cabinet fled the city—humiliated, but unbroken.

In the conflict’s darkest moment, Madison’s resolve held firm. He called for reinforcements, resisted calls for surrender, and watched as American forces turned the tide. The naval victories on Lake Erie, the defense of Fort McHenry, and Jackson’s triumph at New Orleans rekindled national pride.

The Treaty of Ghent, signed in 1814, restored peace without ceding ground. Though no territory changed hands, the war confirmed that the American republic could—and would—defend its sovereignty. Madison emerged weathered, but vindicated.

In its wake, he signed legislation establishing the Second Bank of the United States and protective tariffs to nurture domestic manufacturing—measures he had once opposed, but now deemed necessary for national strength. In war, as in constitution-making, Madison adapted without compromising core principles.

Retirement and Legacy

After leaving office in 1817, Madison returned to Montpelier, where he advised Jefferson and Monroe, corresponded with younger statesmen, and oversaw the organization of his Convention notes for future generations.

In 1829, at seventy-eight, he attended Virginia’s constitutional convention, quietly shaping debates on suffrage and representation. He remained a voice of caution and balance, opposing narrow factions and championing the people’s enduring role in government.

He died on June 28, 1836, at the age of 85—the last surviving signer of the Constitution. His grave at Montpelier bears no titles, only a name.

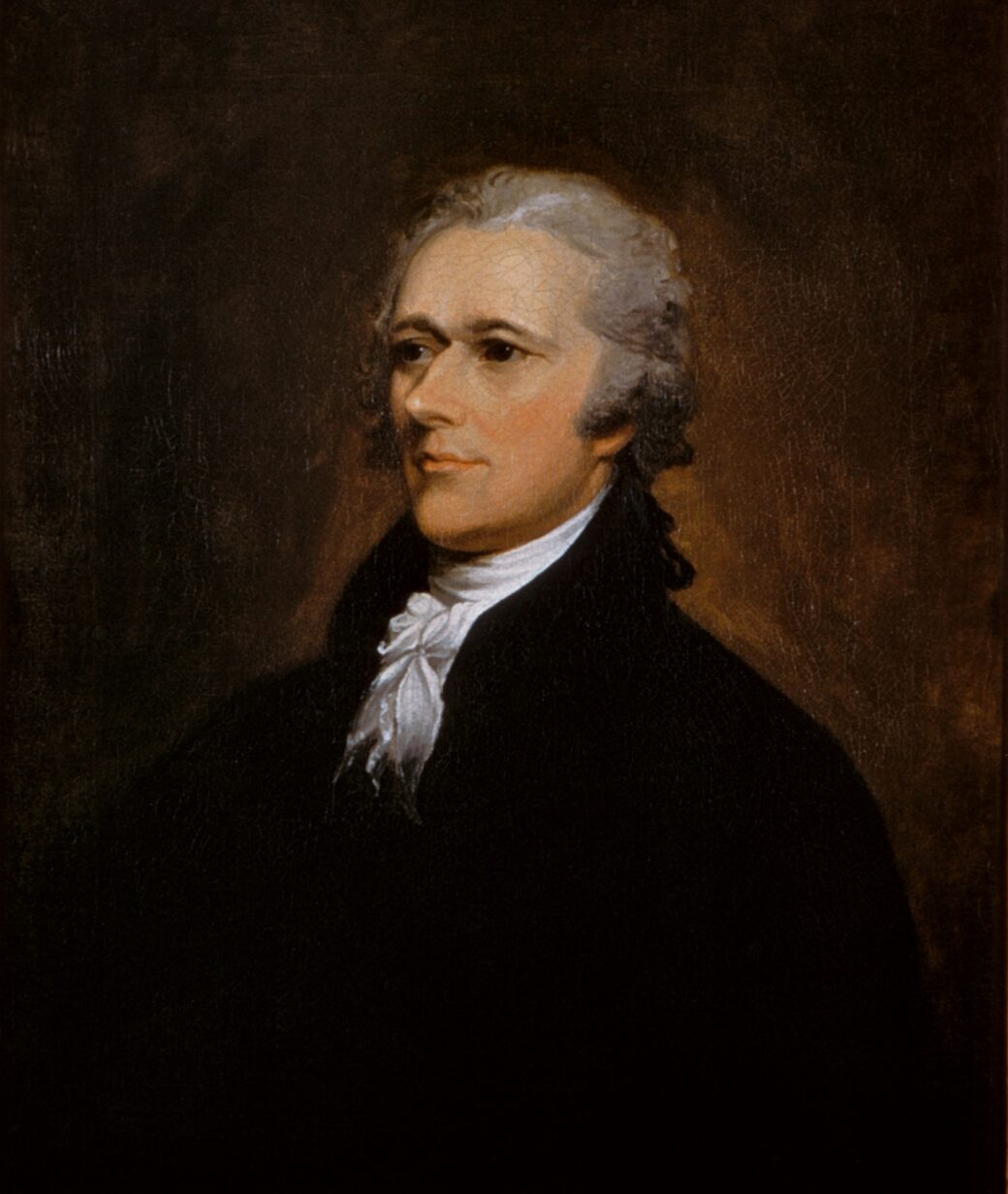

Alexander Hamilton

America’s First Treasury Secretary

A brilliant mind forged in adversity, Alexander Hamilton rose from obscurity to become a towering force in the founding of the American republic. Guided by ambition, intellect, and unrelenting resolve, he envisioned a nation fortified by unity, order, and economic strength—his legacy forever etched into its foundation.

Early Life

Born on January 11, 1755—or 1757, as records dispute—on the Caribbean island of Nevis, Alexander Hamilton entered the world under the shadow of hardship. The illegitimate child of Rachel Faucette and James Hamilton, a Scottish merchant of uncertain fortune, Alexander’s early life was marked by instability.

By age thirteen, he was orphaned—his mother lost to fever, his father long since vanished. Raised briefly by a cousin who soon took his own life, Hamilton found employment as a clerk at the trading firm of Beekman and Cruger in St. Croix. There, he mastered finance, shipping, and trade, displaying a brilliance beyond his years.

His vivid prose and intellect caught the attention of local benefactors. Moved by a letter he penned describing a hurricane that ravaged the island, community leaders raised funds to send him to mainland America. In 1772, he sailed to New York, arriving with little more than ambition and a mind sharpened by self-education.

While lodging with Hercules Mulligan, a tailor and committed patriot, Hamilton enrolled at King’s College—now Columbia University—immersing himself in Enlightenment philosophy, law, and revolutionary thought. The stage for his destiny had been set.

American Revolution

As tensions with Britain escalated, Hamilton emerged as a voice of the resistance, authoring compelling pamphlets in defense of colonial rights. His rebuttals to loyalist Samuel Seabury earned him notoriety and confirmed his standing among the revolutionary intelligentsia.

In 1775, at just 20 years old, he joined a New York militia company, quickly rising to captain of an artillery unit. His command at the Battle of Trenton showcased his valor, earning him the attention of General George Washington.

In 1777, Hamilton was appointed Washington’s aide-de-camp, with the rank of lieutenant colonel. Though confined to administrative duties, his influence was profound—drafting correspondence, organizing logistics, and coordinating military operations at a time when resources were scarce and unity fragile.

Desiring battlefield command, Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton resigned his staff position in 1781. At the Siege of Yorktown, he led a daring assault on British redoubts, helping secure a decisive victory and hastening the end of the war. Disillusioned by the inefficiencies of the Continental Congress, he emerged from the Revolution with a burning belief in the necessity of a strong central government.

Post-War Career

Returning to civilian life, Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler in 1780, joining one of New York’s most influential families. He passed the bar with remarkable speed and opened a thriving legal practice.

Elected to the Confederation Congress in 1782, he grew increasingly frustrated by its impotence—unable to levy taxes or regulate commerce. As a land speculator and economic thinker, he bristled at the instability that plagued the young republic.

The eruption of Shays’ Rebellion in 1786 only deepened his conviction. That same year, he helped convene the Annapolis Convention, laying the groundwork for a Constitutional Convention that would redefine the American experiment.

The Constitutional Convention

In 1787, Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia with a bold plan: a government modeled in part on British strength, proposing a president and senators with life terms. His vision was dismissed as overly aristocratic, but his presence—eloquent, forceful, unwavering—left its mark.

When New York’s other delegates withdrew, Hamilton remained undeterred. His greatest contribution came through the pen. Alongside James Madison and John Jay, he authored the majority of The Federalist Papers, a series of essays defending the proposed Constitution with unmatched clarity.

In Federalist No. 70, Hamilton wrote, “Energy in the executive is a leading character in the definition of good government,” underscoring his belief in effective leadership. Where the Articles of Confederation had failed, he saw structure and strength as the antidote to national chaos.

The Treasury

Appointed the first Secretary of the Treasury by President Washington in 1789, Hamilton moved swiftly to stabilize the infant economy. His plan was ambitious: federal assumption of state debts, the creation of a national bank, and protective tariffs to nurture American industry.

His policies sparked fierce opposition from Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Congressman James Madison, who feared federal overreach. Yet Hamilton’s pragmatism prevailed. In a now-legendary compromise, Jefferson and Madison agreed to support his financial plan in exchange for relocating the national capital to the Potomac—a deal that birthed both the First Bank of the United States and the city of Washington, D.C.

His Report on Manufactures envisioned a robust industrial future, in stark contrast to Jefferson’s agrarian idealism. Resigning in 1795 amid the fallout from his affair with Maria Reynolds—the nation’s first political sex scandal—Hamilton left behind an enduring financial system and a newly defined party: the Federalists.

Foundational Institutions

Hamilton’s imprint extended far beyond economics. In 1790, he founded the Revenue Cutter Service—precursor to the U.S. Coast Guard—to enforce tariffs and protect commerce. He established the Bank of New York in 1784, a commercial institution that continues to this day.

In 1801, he launched the New York Evening Post, a Federalist newspaper designed to influence public thought—a testament to his belief in the power of ideas. Each of these institutions served his greater goal: building a durable American state supported by law, finance, and infrastructure.

Political Influence in the Election of 1800

Though out of office, Hamilton remained a force in national politics. In 1798, he was appointed Major General during the Quasi-War with France, organizing the emerging army with typical precision.

During the tumultuous election of 1800, Hamilton’s distrust of Jefferson was only outmatched by his loathing of Aaron Burr. When the election ended in a tie, it was Hamilton who persuaded Federalists in the House to support Jefferson—“a man of principle”—over Burr, whom he considered dangerously unmoored.

That decision would have lasting consequences.

Duel and Death

Hamilton’s feud with Aaron Burr, once political and now deeply personal, reached its deadly crescendo on July 11, 1804, along the banks of the Hudson River in Weehawken, New Jersey. In the infamous duel, Hamilton was mortally wounded and died the next day at the age of 49.

His death sent shockwaves through the republic. Eulogized and vilified in equal measure, Hamilton left a legacy both complex and colossal.

In 1929, the U.S. Treasury placed his likeness on the ten-dollar bill—a fitting tribute to the architect of its economic foundation. From orphaned clerk to constitutional force, Hamilton’s journey was one of vision and velocity—a life lived on principle, propelled by intellect, and driven by a ceaseless belief in the promise of the American future.

Benjamin Franklin

Writer, Inventor and Statesman

A spark of genius and a cornerstone of liberty, Benjamin Franklin brought restless curiosity and civic purpose to the heart of the American experiment. His inventions illuminated everyday life, his diplomacy secured independence, and his ideas shaped the spirit of a rising republic.

Early Life

Born January 17, 1706, in Boston, Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin was the fifteenth of seventeen children born to Josiah Franklin, a candle-maker, and Abiah Folger, a devout Puritan.

Life was noisy, frugal, and bustling—an education in self-reliance. His formal schooling ended at age ten, but Franklin turned instinctively to books. He devoured works of history, mathematics, and philosophy, forging a mind that would challenge old truths and imagine new systems.

At twelve, he was apprenticed to his older brother James, a printer. The trade taught him to set type and speak plainly—but their partnership frayed. In 1723, at seventeen, Franklin fled to Philadelphia with few coins and even fewer connections. What he carried instead was ambition, wit, and an insatiable drive to make his mark.

Career

Franklin’s rise was not linear—it was expansive. In 1724, he traveled to London, working in print shops and sharpening both his craft and worldview. By 1726, he returned to Philadelphia and launched his own press.

In 1729, he purchased The Pennsylvania Gazette, transforming it into the most influential paper in the colonies. With crisp writing and bold ideas, it became a vessel for public discourse. His 1733 Poor Richard’s Almanack, filled with homespun proverbs and wry wisdom, spread his fame far beyond Pennsylvania.

Science enthralled him. In 1752, he conducted his famed kite experiment, proving lightning to be electrical and earning accolades from Europe’s learned societies. He explored currents, mapped the Gulf Stream, and studied weather patterns—his intellect unbounded by any one discipline. He founded the Junto, a club of artisans and thinkers committed to mutual improvement and civic reform.

By the 1750s, Franklin had become not just a printer and scientist, but a statesman—serving in the Pennsylvania Assembly and managing a growing business empire.

Inventions

Franklin’s inventions were pragmatic, democratic, and never patented—his goal was utility, not profit. In 1741, he created the Franklin stove, a metal fireplace designed to heat homes more efficiently.

In 1752, he introduced the lightning rod, a simple yet revolutionary safeguard against fire from storm strikes. Later, he devised bifocals to ease aging eyes, a flexible catheter for his ailing brother, and an odometer to improve mail routes.

He believed ideas were for the common good—his inventions reflected that creed.

Public Life

Franklin’s public service was driven by practical idealism. In 1731, he founded America’s first lending library in Philadelphia. In 1736, he organized the Union Fire Company—one of the colonies’ earliest volunteer fire brigades.

Appointed Philadelphia’s postmaster in 1737, he later became joint postmaster general for the colonies in 1753. Under his tenure, the postal service expanded, speeding communication across the Atlantic world.

At the 1754 Albany Congress, he proposed a plan for colonial union—ahead of its time, but signaling his capacity for strategic thought. By 1757, Franklin was in London, representing Pennsylvania and soon other colonies, navigating the turbulent politics of empire and taxation.

American Revolution

Franklin remained in London until 1775, lobbying for colonial rights with his trademark diplomacy and wit. He supported the Olive Branch Petition in a final effort to avoid war. When King George III rejected it, Franklin returned home—resigned, yet resolute.

He joined the Second Continental Congress and was appointed to the committee drafting the Declaration of Independence. At 70 years old, he signed his name to treason. His editorial revisions sharpened the language, giving the document its moral clarity.

Later that year, Congress sent him to France. His charm, intellect, and fame captured the imagination of the French court. He secured vital loans, military support, and alliances—turning the tide of the war and ensuring American victory at Yorktown.

Post-War Roles

Franklin remained in France to help negotiate the 1783 Treaty of Paris, concluding peace with Britain. Alongside Adams and Jay, he secured not only independence but generous borders and fishing rights. He stayed until 1785, cementing trade agreements and cultivating goodwill with America’s oldest ally.

Back in Philadelphia, he watched as unrest brewed—most notably Shays’ Rebellion in 1786. He interpreted it not as a threat but as a reminder that liberty requires vigilance.

From 1785 to 1788, he served as President of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council—effectively the state’s governor—where he promoted road improvements, reduced taxes, and supported public education.

Constitutional Convention

In 1787, at the age of 81, Franklin was the oldest delegate to the Constitutional Convention. Though too frail to stand and speak often, his presence carried immense weight.

He proposed a bicameral legislature to balance the power of large and small states and called for prayer during heated debates, appealing for humility in service of unity.

Franklin signed the Constitution with hope—not certainty—but confidence that compromise could secure the republic’s future.

Death

Franklin retired from public life in 1788, turning his attention to writing, science, and reflection. He completed his Autobiography, a guide as much for citizens as for posterity, full of maxims on thrift, merit, and moral progress.

He died on April 17, 1790, at the age of 84. More than 20,000 mourners attended his funeral in Philadelphia—a testament to the esteem he commanded across class and continent.

In his will, he left £1,000 each to Boston and Philadelphia to be invested for 200 years. By 1990, those funds had grown into millions—financing scholarships, libraries, and vocational training, continuing the work of a man who believed the surest way to build a better world was to enlighten it.

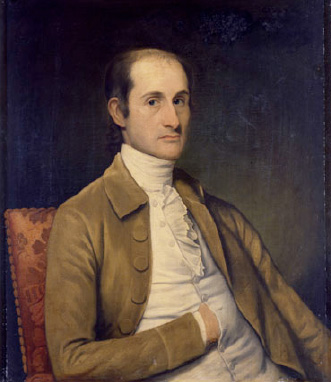

John Jay

America’s First Chief Justice

Diplomat turned statesman, John Jay stands among the Founders as a steward of law and calm—an architect of peace, order, and principle. From courtrooms to Congress, from Paris to London, he guided the young republic with the conviction that justice, not fury, would hold a nation together.

Early Life

Born December 12, 1745, in New York City, John Jay was the sixth of ten children to Peter Jay, a prosperous merchant, and Mary Van Cortlandt, descended from one of New York’s oldest Dutch families. Smallpox forced the family from the city to Rye, where Jay spent much of his youth in quiet study and country air.

Educated at home by private tutors, he mastered Latin, Greek, and philosophy before entering King’s College (now Columbia University) in 1760. He graduated in 1764 with a lawyer’s logic and a reformer’s temperament. Called to the bar in 1768, he entered public life at the brink of revolution—his mind wired for structure, even as the world came unglued.

Path to Revolution

In the early 1770s, Jay built a respected legal career in New York while gravitating toward the cause of liberty. He joined the Committee of Correspondence in 1774 and attended the First Continental Congress that fall, urging moderation but insisting on rights. That same year, he married Sarah Livingston, daughter of New Jersey’s governor—an alliance that deepened his roots in the region’s political elite.

Though inclined to avoid war, Jay’s legal mind recoiled at British overreach: the Stamp Act, the Quartering Act, the Intolerable Acts. He drafted addresses to the British crown pleading for reconciliation—reasoned arguments that would soon be cast aside.

In 1776, as a delegate to New York’s Provincial Congress, he helped draft the state’s constitution. War had come, and Jay no longer sought peace—he sought structure, stability, and sovereignty.

American Revolution

When independence was declared, Jay returned to Congress as a leading voice for civil order amid chaos. Appointed Chief Justice of New York in 1777, he battled both British invasion and Loyalist backlash in the courts—upholding law while war raged beyond the bench.

In 1778, he was elected President of the Continental Congress, a ceremonial but symbolic role during a time of fracture and fatigue. The next year, Congress sent him to Spain to secure diplomatic recognition and financial aid. Though Spain offered little, Jay’s resolve held. He moved to Paris in 1782, joining Franklin and Adams to negotiate the Treaty of Paris.

His insistence on direct dealings with Britain—refusing to let France sideline American interests—proved decisive. The final treaty secured independence, ceded western lands to the Mississippi, and guaranteed fishing rights—wins not of cannon fire, but of quiet leverage.

Post-War Diplomacy and Constitutional Influence

Returning home in 1784, Jay became Secretary for Foreign Affairs under the Articles of Confederation. His post, prestigious in name, was powerless in practice. British troops lingered in western forts, Spain blocked the Mississippi, and the states bickered endlessly.

Shays’ Rebellion in 1786 confirmed his fears. In a letter that year, he warned of “disorder and distrust,” urging stronger federal authority. Though not a delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Jay was a vocal advocate for ratification. Alongside Madison and Hamilton, he co-authored The Federalist Papers, writing five essays—chiefly on foreign affairs and national unity.

His voice was quieter than others, but essential: calm in argument, precise in logic, always seeking structure to match principle.

Chief Justice and the Jay Treaty

In 1789, President Washington appointed Jay the first Chief Justice of the United States. He helped implement the Judiciary Act of 1789, establishing the federal court system and setting the foundation for judicial review and national supremacy.

Jay presided over Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), a landmark case affirming that citizens could sue states—provoking public backlash and the passage of the 11th Amendment, but proving the court’s reach. In Hayburn’s Case, he pushed back against congressional efforts to enlist judges in administrative roles, asserting the independence of the judiciary—a cornerstone principle ever since.

In 1794, with tensions rising between the U.S. and Britain, Jay was sent to London as special envoy. Jay’s Treaty—deeply controversial—avoided war, forced Britain to evacuate western forts, and secured trade concessions. Critics howled that it gave too much, but Washington backed it as essential. Jay returned home to protests, but history vindicated the effort: it preserved peace and reinforced American sovereignty.

Governor and Final Years

In 1795, while still abroad, Jay was elected Governor of New York. He resigned from the Supreme Court and served two terms, reforming the state’s judiciary, promoting education, and curbing slavery. He signed legislation that began New York’s gradual emancipation in 1799—a quiet milestone in the long road toward liberty.

In 1801, Jay declined an offer to return as Chief Justice. He had done enough. He retired to his farm in Bedford, New York, where he lived simply, reflecting on a life of public service.

He remained politically active, writing against the War of 1812 and advocating for national unity. He passed away on May 17, 1829, at the age of 83, outliving all but a few of his contemporaries.

His name adorns courthouses, colleges, and treaties—in every courtroom, in every peaceful negotiation, John Jay’s legacy echoes—not in volume, but in permanence.