Signers of the

Declaration of Independence

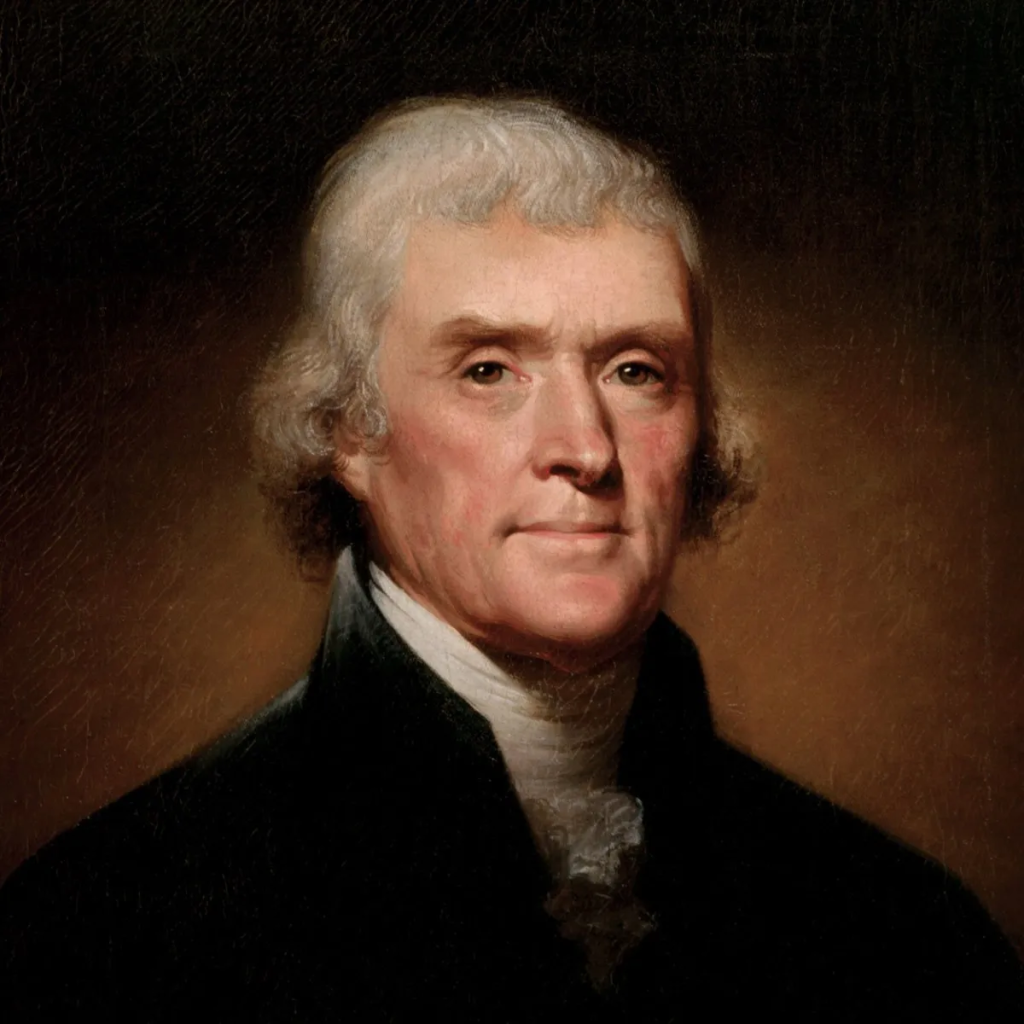

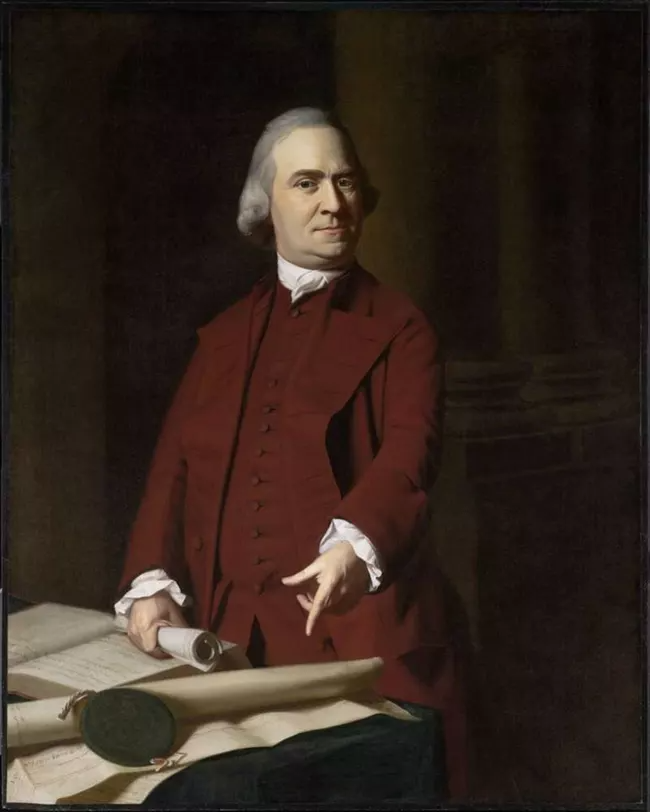

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826)

Born on April 13, 1743, near present-day Charlottesville, Virginia, Thomas Jefferson was the primary drafter of the Declaration of Independence and the third President of the United States. The son of Peter Jefferson, a farmer and surveyor, and Jane Randolph, who hailed from a prominent Virginia family, Jefferson was educated by private tutors.

He later attended the College of William and Mary, where he studied mathematics, philosophy, law, and languages. A man of the Enlightenment, he inherited a large estate from his father and designed his lifelong residence, Monticello.

At 26, Jefferson entered the Virginia House of Burgesses, where his eloquence earned him a seat in the Second Continental Congress. At 33, he agreed to draft the Declaration of Independence upon John Adams’s insistence that Jefferson was more eloquent and well-liked than him. He penned the words that inspired thousands of young men to give their lives for the ideals that still ring true in the heart of every American: “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Following a term as Governor of Virginia, Jefferson became Minister to France, strengthening ties with America’s key wartime ally. Under George Washington, he served as the first Secretary of State. In 1796, Jefferson was elected Vice President under John Adams, and in 1800, he defeated Adams in a fiercely contested election. As President, Jefferson orchestrated the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the nation’s size, and pursued neutrality during the Napoleonic Wars.

After two terms, he retired to Monticello, where he corresponded with former rival John Adams. Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. According to one account, just before he died, he asked his physician, “Is it the Fourth?”

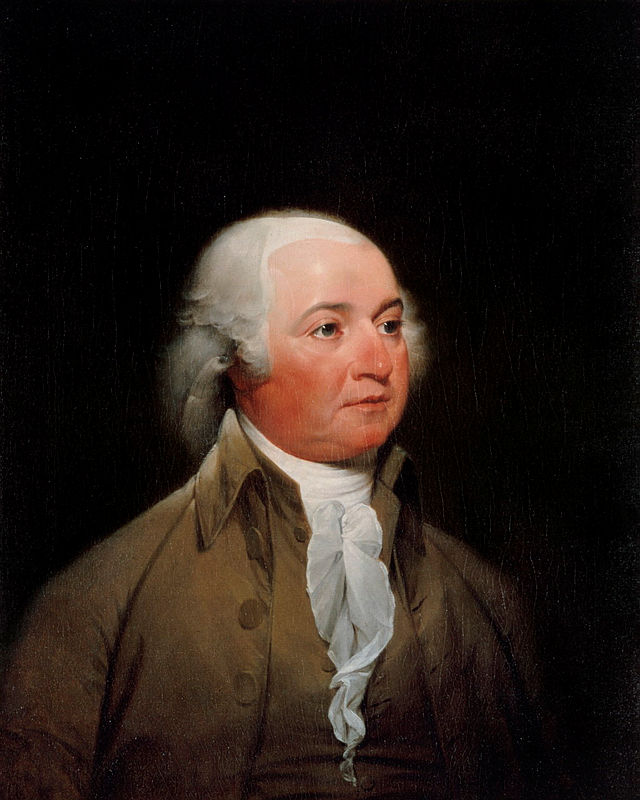

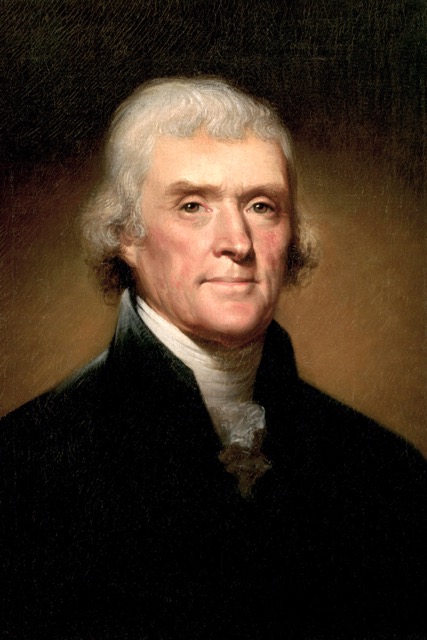

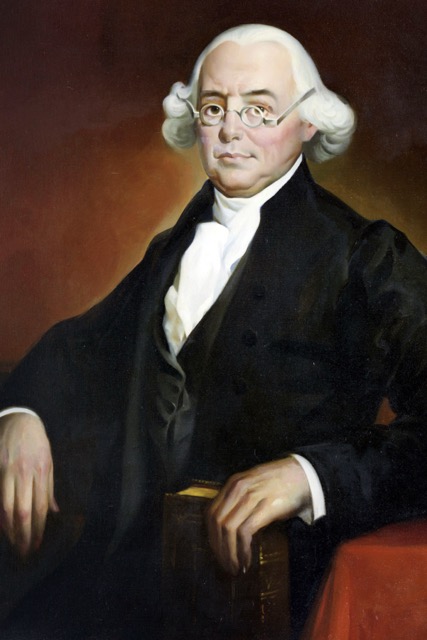

John Adams (1735-1826)

John Adams was a lawyer, statesman, and political theorist whose writings and intellect were vital to American independence.

Born on October 30, 1735, in Braintree, Massachusetts, Adams attended Braintree Latin School and entered Harvard College at 16, later studying law and opening a practice in 1758. In 1764, he married Abigail Smith, with whom he had six children.

Though initially hesitant to enter politics, the Stamp Act of 1765 spurred Adams to write essays supporting the Patriot cause and he became one of the most prominent voices for independence. Despite his fierce opposition to British rule, he defended the British soldiers in the Boston Massacre, believing that no one should be denied the right to a fair trial.

In 1774, Adams was selected as one of Massachusetts’ delegates to the First Continental Congress. He returned the following year for the Second Continental Congress, where he helped draft the Declaration of Independence. Adams wrote Abigail, “The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha in the History of America.” In 1789, Adams became the first Vice President, serving under George Washington. He was inaugurated as President on March 4, 1797. He avoided war with France and preserved national unity during a volatile period. He was the first president to live in the White House, leaving office in 1801.

In later years, Adams renewed his friendship with his political rival, Thomas Jefferson. On July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration, Adams died at age 90, reportedly saying, “Jefferson still survives.” Unbeknownst to him, Jefferson had died hours earlier that same day.

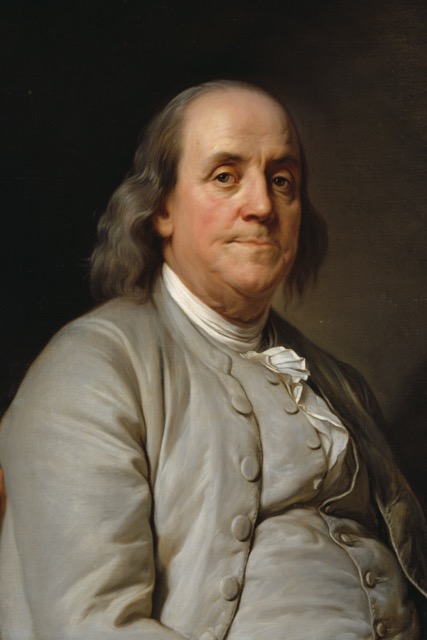

Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790)

Benjamin Franklin—printer, writer, inventor, diplomat, and Founding Father—was the most widely recognized American on the world stage at the birth of the United States. His wisdom and dedication to liberty helped shape the foundations of American democracy. Born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, Massachusetts, Franklin was the fifteenth of seventeen children. At 12, he apprenticed in his brother’s printing shop. At 17, he moved to Philadelphia, where he launched a successful printing business and published the widely read Poor Richard’s Almanack.

A self-taught scientist, Franklin gained international fame for his inventions, including the lightning rod, bifocal glasses, the Franklin stove, a musical instrument, and his kite-and-key experiment, which demonstrated that lightning is a form of electricity. Franklin also helped build American civic life. He helped found the first public lending library, created the first volunteer fire department, helped establish the University of Pennsylvania, and supported the chartering of the first public hospital.

At 70, Franklin was the oldest delegate to the Second Continental Congress and served on the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence. Soon after its signing, he sailed to France, where he played a crucial role in securing French support for American independence.

In 1787, Franklin served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention at age 81, becoming one of only six men to sign both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. At the Convention’s close, when asked what kind of government had been created, he replied, “A republic, madam—if you can keep it.”

Franklin died on April 17, 1790, at the age of 84. More than 20,000 people attended his funeral in Philadelphia.

John Hancock (1737-1793)

John Hancock, born on January 23, 1737, in Braintree, Massachusetts, is widely remembered for his prominent signature on the Declaration of Independence. His contributions to the founding of the United States extended far beyond that moment.

After his father’s death in 1744, Hancock was raised by his wealthy uncle, Thomas Hancock, a successful Boston merchant. This afforded him a strong education, and he graduated from Harvard College in 1754 at age 17. He then apprenticed in his uncle’s mercantile business and upon his uncle’s death in 1764, inherited a large estate, becoming one of the wealthiest men in the colonies.

Hancock entered politics in 1765, holding several local offices before joining the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, the colony’s Patriot-led governing body. He actively opposed British taxation policies, including the Stamp Act, and supported boycotts against British imports.

In 1768, British officials seized Hancock’s ship, the Liberty, for allegedly smuggling wine. Though charges were dropped, the event galvanized colonial resistance and raised Hancock’s profile as a Patriot leader.

Hancock was elected to the Continental Congress, serving twice as its president between 1775 and 1786. On July 4, 1776, he became the first to sign the Declaration of Independence, with a signature famously so large, that as legend has it, King George III would be able to see it without reading glasses.

After the war, Hancock returned to Massachusetts, where he served multiple terms as governor from 1780 until his death in 1793. He played a key role in Massachusetts’ ratification of the U.S. Constitution and supported the Bill of Rights. Hancock died on October 8, 1793, at age 56.

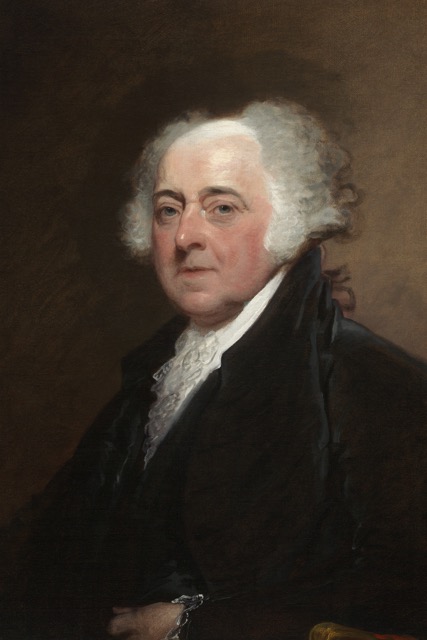

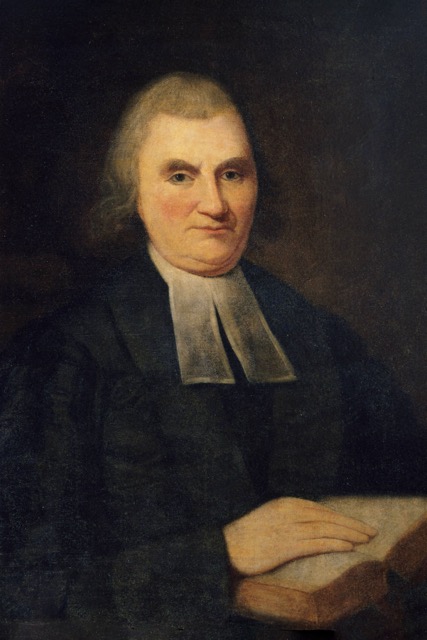

Samuel Adams (1722-1803)

Samuel Adams, born on September 27, 1722, in Boston, Massachusetts, was a passionate and influential voice against British rule before and during the American Revolution. A second cousin of President John Adams, he played a major role in advancing the cause of independence.

The son of Puritan parents, Adams was raised with strong religious values. Initially expected to become a minister, he graduated from Harvard College in 1740 and later turned to politics. He was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives and later served in the Continental Congress. By the 1770s, he had become one of the leading advocates for American independence.

Adams was a founding member of the Sons of Liberty, the group that famously organized the Boston Tea Party, destroying British tea in protest of new taxes.

Adams participated in the First and Second Continental Congress, signing the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Due to his strong opposition to British rule, he was viewed as a major threat to the Crown—so much so that British authorities offered pardons to all who laid down their arms after the Battle of Lexington and Concord except Adams and John Hancock.

After the war, Adams helped draft the Massachusetts state constitution and served as governor of Massachusetts. He died on October 2, 1803, at the age of 81. His hometown newspaper remembered him as the “Father of the American Revolution.”

Josiah Bartlett (1729 – 1795)

Josiah Bartlett was a physician, statesman, and Patriot whose intellect and vision earned him a place among the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Born on November 21, 1729, in Amesbury, Massachusetts, Bartlett began studying medicine at the age of 16, practicing under several local doctors before establishing his own practice in Kingston, New Hampshire. Pioneering new ways to treat common ailments such as fevers and diphtheria, Bartlett quickly earned the respect of his adoptive colony as a skilled doctor.

Bartlett’s influence extended beyond his medical practice. In the 1760s, as tensions with Britain increased, Bartlett was elected to the colonial assembly. In 1774, he became such a fervent advocate for American independence that when voting for independence Bartlett reportedly “made the rafters shake with the loudness of his approval.” He was among the first to vote for independence in 1776, and risked his own personal safety by enlisting in the New Hampshire state militia. At one point, Bartlett’s home was burned to the ground, likely by British loyalists.

Bartlett played a key role in drafting the New Hampshire state constitution and served as Chief Justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court. In 1790, he became the first governor of New Hampshire. He died on May 19, 1795, at the age of 65, but his contributions in medicine and politics fundamentally shaped our nation.

Carter Braxton (1736 – 1797)

Carter Braxton was a wealthy landowner, businessman, and financier of the American Revolution. Born on September 10, 1736, at Newington Plantation in Virginia, Braxton graduated from the College of William and Mary in 1755. At 19, he married into another influential family, further elevating his social standing. Tragedy struck when his wife died after two years, leaving him with two daughters. To recover, he spent time in England, where he became familiar with British politics and its colonial policies.

After remarrying, Braxton resumed life as a planter and businessman in Virginia. As tensions with Britain escalated, he joined the Virginia House of Burgesses and in 1776 was appointed as a delegate to the Continental Congress. Though initially reluctant, he came to support independence and signed the Declaration of Independence, risking his wealth and status in the process.

Braxton invested heavily in the Patriot cause, funding the Continental Navy and military efforts. Many of his ships and ventures were lost to British blockades and wartime destruction. Once one of Virginia’s wealthiest men, he took on tremendous debt due to his commitment to the cause.

After the war, Braxton continued to serve in the Virginia state government. He died on October 10, 1797, at the age of 61, having sacrificed much of his fortune in support of American freedom.

Charles Carroll of Carrollton (1737-1832)

Charles Carroll of Carrollton was the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence. Born on September 19, 1737, in Annapolis, Maryland, Carroll was one of the wealthiest and most educated men in the colonies; he was a powerful voice for freedom, religious liberty, and Maryland’s place in the new nation.

Educated in Europe in liberal arts and civic law, Carroll returned to Maryland at age 28, only to find himself barred from public office due to his Catholic faith. This did not prevent Carroll from amassing a fortune through agricultural estates and financing new businesses. He was reportedly worth $375 million in today’s dollars. His family had long hoped Maryland would one day serve as a haven for persecuted Catholics—a vision Carroll helped bring to life through steadfast service and sacrifice.

In 1773, Carroll rose to prominence as a public advocate for colonial rights, writing under the pseudonym “First Citizen” in the Maryland Gazette. He played a crucial role in securing Maryland’s resolution for independence and served in the Second Continental Congress, where he risked his life and fortune to sign the Declaration of Independence. As one spectator is said to have remarked after Carroll signed onto the Declaration, “There go a few millions.”

Carroll was a major financier of the Revolution. He helped draft the Maryland Constitution and was instrumental in the state’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution. From 1789 to 1792, he served as Maryland’s first U.S. Senator.

Devoted to God, family, and country, Charles Carroll lived to the remarkable age of 95, dying on November 14, 1832, as the longest-living and last surviving signer of the Declaration.

Samuel Chase (1741-1811)

Samuel Chase, one of the nation’s first major legal figures, played a key role in the early formation of the American Republic and its legal system.

Born on April 17, 1741, near Princess Anne, Maryland, Chase was the only child of Thomas Chase, an Anglican minister, and Matilda Walker. Educated at home, he studied law in Annapolis and was admitted to the bar in 1761 at age 20. He became known for representing middle-class clients, often pro bono, and quickly built a strong reputation as a lawyer.

At 23, Chase was elected to the Maryland General Assembly, where he served from 1764 to 1784. He became a vocal opponent of British rule, particularly following Parliament’s imposition of the Stamp Act in 1765. He served in the First and Second Continental Congress, where he joined Franklin and Carroll on a trip to persuade the Canadians to join the American Revolution. The attempt was unsuccessful.

After the war, Chase continued his legal career and in 1796 President George Washington appointed him a Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. A committed Federalist, Chase’s political views on the bench drew criticism, and in 1804, he was impeached by the House of Representatives under the leadership of President Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party.

Chase was charged with eight counts, including refusing to dismiss biased jurors and promoting political opinions from the bench. The Senate acquitted him on all counts, with several senators voting against his impeachment despite party affiliation. The impeachment trial set precedents on the need for judges to refrain from advancing partisan politics from the bench, and it also further enshrined the independent nature of the judiciary. Chase remained on the Supreme Court until his death on June 19, 1811.

Abraham Clark (1726-1794)

Abraham Clark was born on February 15, 1726, in present-day Elizabeth, New Jersey. With little formal education and chronic illnesses that made farm work difficult, he pursued independent study and developed strong skills in mathematics. He became known as a “poor man’s counselor,” offering legal advice—often for free—despite likely never being formally admitted to the bar.

Clark married Sarah Hatfield, and they had ten children. He began his public career as high sheriff of Essex County before joining the New Jersey colonial legislature in 1775.

When New Jersey’s original delegates opposed independence at the Continental Congress, the state convention replaced them with six new delegates, including Clark. He signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and remained a steady presence in the Continental Congress, often serving simultaneously in the state legislature. During the war, two of his sons were captured and imprisoned by the British aboard the Jersey prison ship.

After the war, Clark was one of twelve delegates to attend the Annapolis Convention of 1786, addressing the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. Though illness prevented him from attending the Constitutional Convention, he lobbied for the inclusion of a Bill of Rights.

In later years, Clark was elected to the Second and Third U.S. Congresses. He died of heat stroke on September 15, 1794, having dedicated his life to the birth of this new nation.

George Clymer (1739-1813)

George Clymer, a grandson of an original settler of the Penn colony, became an orphan at the age of one. He went to live with a wealthy uncle in Philadelphia, where he received an informal education and he grew up working in his uncle’s mercantile firm. His exposure to business and finance would later serve Clymer well in his roles as a leading Philadelphia merchant and a key figure in the Revolutionary cause.

An early patriot, Clymer abhorred the restrictive economic policies of the British, which threatened his business interests. After serving on the Philadelphia Committee of Safety, his expertise in financial matters made him a natural choice for the Continental Congress, where he signed the Declaration of Independence and served as one of the first two Continental treasurers. There, Clymer made significant contributions, personally underwriting the war effort by exchanging his specie for Continental currency. When British forces threatened to occupy Philadelphia, some members of the Continental Congress fled to Baltimore, but Clymer courageously stayed behind with George Walton and Robert Morris.

After the war, Clymer continued to serve in various capacities, including the Pennsylvania legislature, where he advocated for penal code reform. He also represented Pennsylvania in the Constitutional Convention and later served as a United States Representative in the First Congress. Later in life, he accepted a series of appointments and advanced various community projects. He died at the age of 73 in 1813. His legacy remains a testament to the enduring power of commerce, patriotism, and public service.

William Ellery (1727-1820)

Born on December 22, 1727 in Newport, Rhode Island, Ellery followed in the footsteps of his father, a prominent merchant and political leader, attending Harvard at the age of 16. After graduating in 1747, he returned home and tried his hand at several occupations, eventually taking up the study of law in 1770.

Renowned for his support of Patriot causes, Ellery was selected as a delegate for the Second Continental Congress, where he earned a reputation for his witty epigrams. He’s cited as calling the Declaration of Independence a “Death Warrant.” Yet, Ellery signed with undaunted resolution. Through his epigrams, he brought humor and friendly banter to Congress. For instance, in the below epigram Ellery criticized his colleague from Philadelphia, Andrew Allen, who was reluctant to sign the Declaration.

A Commissioner, to the people of P _ _ _ _ _ a

Attend all ye People of ev’ry degree

No longer pretend that your Country you’ll free

Declare for your Treasons a hearty Contrition

Regard as you tender your lives Admonition

E‘re too late to flee from impending Perdition

Who like me to the King Allegiance will swear

And future Submission to Congress forbear

Leave all his old Friends to the Parliaments Fury

Let Rebels be hang’d without Judge or Jury

Escapes condemnation to gibbet or halter

Nor needs forfeiture fear unless times should alter.

Ellery lived to the age of 92, keeping active in public affairs, and spending many hours in scholarly pursuits and correspondence.

William Floyd (1734–1821)

William Floyd was born on December 17, 1734, on Long Island, New York, the second of nine children. His father, a successful farmer of Welsh descent, raised the family with a strong work ethic and practical education. When Floyd’s parents died in 1755, he inherited the family estate and took responsibility for his siblings. He married in 1760 and managed both the farm and family.

Floyd became a respected figure in his community and helped lead the local militia, attaining the rank of Colonel in 1775. He supported the Patriot cause early, attending meetings opposing the British closure of the Port of Boston.

In 1774, Floyd was chosen to represent Suffolk County in the Continental Congress, where he served until 1777 and again from 1779 to 1783. During the war, he also held the rank of Major General in the militia.

While Floyd served in Congress, the British occupied his home, converting it into a barracks. He fled to Connecticut with his wife and three children. The hardships of war took a toll on his family; his wife died in 1781 after prolonged illness and stress.

After the war, Floyd served several terms in the New York State Senate, supported the U.S. Constitution, and participated in the New York Constitutional Convention of 1801. He was elected to the First U.S. Congress, serving from 1789 to 1791.

In later life, Floyd invested in land in central New York, securing a state grant of over 10,000 acres. He spent summers developing the property and eventually relocated there, building a home near present-day Westerville, New York. He died in 1821 at the age of 86.

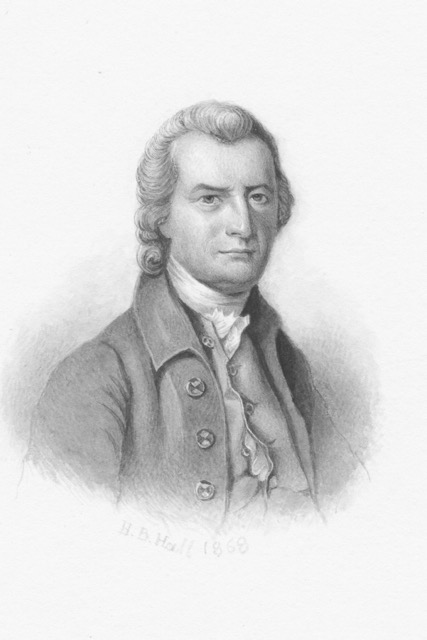

Elbridge Gerry (1744–1814)

Elbridge Gerry was a merchant, politician, and diplomat who served as the fifth vice president of the United States.

Born on July 17, 1744, in Marblehead, Massachusetts, Gerry came from a family of successful merchants. He graduated from Harvard College and worked closely with Samuel Adams. After a brief time in commerce, he entered public service as a member of the Massachusetts Legislature and General Court.

In 1775, Gerry was elected to the Second Continental Congress, where he signed the Declaration of Independence, and continued to serve until 1780.

In response to Shays’ Rebellion, Gerry was selected to attend the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He chaired the committee that helped forge the Great Compromise, which created a bicameral legislature with popular representation in the U.S. House of Representatives and equal representation for each state in the Senate.

Concerned about centralized power, Gerry—along with Edmund Randolph and George Mason—refused to sign the Constitution without a Bill of Rights. After ratification, he served two terms in Congress, retiring in 1793.

In 1797, Gerry participated in a diplomatic mission to France that resulted in the “XYZ Affair,” a scandal in which French agents demanded bribes from American envoys as a condition for negotiations—sparking public outrage in the United States. He later served as Governor of Massachusetts beginning in 1810, where the state legislature’s redistricting decisions led to the term “gerrymandering.” In 1813, he became vice president under James Madison, serving until his death in 1814 at age 70.

Button Gwinnett (1735-1777)

Button Gwinnet was born in 1735 in Gloucestershire, England, to Anne and the Reverend Samuel Gwinnett, a minister in the Church of England. After Gwinnett married and had three children, he sailed to Georgia in 1765 in search of better business opportunities.

After struggles with his merchant business, Gwinnett purchased St. Catherine’s Island off the coast of Georgia, near the booming port of Sunbury, where he became a planter. Gwinnett also became active in local Georgia politics, and was elected to the Commons House of Assembly in 1769. After personal and financial struggles, Gwinnett stepped back from the political scene. But when tensions rose with England, he re-entered the political arena and united coastal and rural dissidents. He was elected commander of Georgia’s Continental Battalion.

After signing the Declaration, Gwinnett returned to Georgia, where he was elected Speaker of the State Assembly and helped draft the state’s first constitution. He was also appointed the provisional president and commander in chief of Georgia, where he was responsible for the unsuccessful invasion of British East Florida.

The backlash from this failed invasion escalated a longstanding feud between Gwinnett and General Lachlan McIntosh, who offered a scathing criticism of Gwinnett’s handling of the invasion, calling him a “scoundrel and lying rascal.” These derogatory comments prompted an outraged Gwinnett to challenge McIntosh to a duel, and on the morning of May 16, 1777, the two men met in Sir James Wright’s Pasture, and standing just 12 feet apart, fired shots at each other. While both were hit, only Gwinnett’s wound would prove to be fatal. He died three days later.

Lyman Hall (1724-1790)

Lyman Hall was born in Wallingford, Connecticut, on April 12, 1724, as the fourth of eight children. He pursued his studies at Yale College, where he graduated in 1747. He became an ordained Congregational minister, but soon pursued a career in medicine, receiving the degree of Doctor of Medicine. His first wife, Abigail Burr, died just a year after their marriage, and in 1753, Hall married Mary Osborn, and they had one son.

In the late 1750s, Hall moved to Georgia, and he became a leading physician in the area. This reputation, along with his charisma, made him a popular and well-established gure among those living in St. John’s Parish. When tensions began to rise against the King, Hall expressed his discontent with the monarch and soon became a spokesman for the Puritan discontent against the crown.

He was elected to the Second Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence— one of four practicing physicians to do so. In January 1783, Hall was elected Governor of Georgia, where he had to address an onslaught of crises, including frontier problems with the Loyalists and Native Americans. He also played a crucial role in establishing the University of Georgia.

After serving as Governor, he moved to Burke Country in 1790, where he died on October 19 of that year, at the age of 66.

Benjamin Harrison V (1726-1791)

Benjamin Harrison V was born on April 5, 1726, at Berkeley Plantation in Virginia. His father, Benjamin Harrison IV, held public office as both the Sheriff of Charles City County and a member of the House of Burgesses. Harrison attended William and Mary College, where he met future revolutionaries like Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson, but he soon had to leave school after his father and a sister were killed by a lightning strike. He returned home to manage the family’s 1,000-acre estate, including shipbuilding and horse breeding.

In 1748, Harrison married Elizabeth Bassett, niece of Martha Washington. They had eight children, including William Henry Harrison, who became the 9th president in 1841, and his great-grandson Benjamin Harrison, who became the 23rd president in 1889.

Harrison entered politics in 1749 as a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he began opposing British rule in the 1760s. When the House passed resolutions condemning the Stamp Act, the Royal Governor tried to sway Harrison with an executive council appointment, but Harrison declined.

After the House was dissolved in 1774, Harrison was elected to the Continental Congress, and in 1776, he signed the Declaration of Independence. He returned to Virginia politics in 1777 and served as a militia lieutenant.

In 1778, Harrison was elected Speaker of the Virginia House, and in 1781, became Governor of Virginia, serving three terms. In 1788, he took part in the Virginia Ratifying Convention, advocating for protections that would later form the Bill of Rights.

Harrison returned to private life and died in Virginia on April 24, 1791, at age 65.

John Hart (1713-1779)

John Hart was born in Stonington, Connecticut, in 1713. His father, Edward Hart, was a farmer, justice of the peace, and public assessor. Soon after John’s birth, the family moved to Hopewell, New Jersey, where Hart would reside for the rest of his life. In 1739, he married Deborah Scudder, and together they had 13 children.

In 1740, Hart began acquiring property, purchasing a 193-acre homestead in Hopewell. Over time, he expanded his holdings and emerged as a respected public figure. He served in various roles, including justice of the peace, county judge, colonial legislator, and judge of the court of common pleas.

As tensions with Britain grew, Hart opposed taxation and the stationing of British troops. In June 1776, he was selected as one of five delegates to represent New Jersey at the Continental Congress, where he signed the Declaration of Independence. Shortly after, he returned to New Jersey to serve as Speaker of the General Assembly.

In October 1776, John Hart returned home from the Continental Congress to attend to urgent family matters. His wife, Deborah, who had been gravely ill, died on October 8 with John at her side. Later that year, John Hart was forced to flee his home as the British invaded Hopewell. After American victories at Trenton and Princeton, Hart returned and was re-elected Speaker, serving until November 7, 1778.

In June 1778, Hart invited George Washington and the Continental Army to encamp on his farm before the Battle of Monmouth. Washington and 12,000 troops stayed for several days before marching to victory. John Hart died of kidney stones on May 11, 1779.

Joseph Hewes (1730-1779)

Joseph Hewes, one of three North Carolinians to sign the Declaration of Independence, advanced the Revolution through his invaluable support of the burgeoning American Navy. He invested his own wealth, leveraged his business network, and sacrificed personal profit to serve the cause of liberty.

Born on January 23, 1730, near Princeton, New Jersey, Hewes grew up in a Quaker family. He received a strict religious upbringing and a standard public education. Sometime around 1750, Hewes moved to Philadelphia to gain experience in the fields of shipping and businesses. There, he served as an apprentice to a successful merchant and importer, Joseph Ogden.

In 1760, Hewes moved to North Carolina, where he built numerous prosperous mercantile businesses. After partnering with Robert Smith, a lawyer friend, he expanded his enterprise and bought a wharf complete with a small fleet. Hewes became engaged, but his fiancée died before their wedding, and he remained a bachelor for the rest of his life.

Three years after his arrival in Edenton, North Carolina the community elected Hewes as a member of the Assembly of North Carolina where he served from 1766 to 1775. There, he helped prepare the “Halifax Resolves,” a report he later presented to the Continental Congress. He was also involved in drafting the “Olive Branch Petition,” carefully outlined grievances against Britain and justified severing ties with the mother country. King George rejected it immediately.

In 1775, North Carolina elected Hewes to the Second Continental Congress where he served as a member of the committee of claims, helped lay the foundations of the Navy, and sat on the committee to prepare the Articles of Confederation. After a long illness, Hewes died on November 10, 1779.

Thomas Heyward Jr. (1746-1809)

Thomas Heyward Jr. was born on July 28, 1746, at his family’s estate in St. Luke’s Parish, South Carolina. His father, Colonel Daniel Heyward, was a successful planter and businessman. Raised in a politically engaged household, Heyward received a legal education at Middle Temple in London, where he developed a strong understanding of governance and became critical of the Crown.

Upon returning to South Carolina, Heyward joined the revolutionary movement and became an active voice for independence. In 1776, he was elected to the Second Continental Congress, where he signed the Declaration of Independence.

During the war, Heyward served as a Captain of Artillery in the South Carolina Militia and was wounded at the Battle of Beaufort. He was later captured by British forces at the Siege of Charleston and held as a prisoner of war in St. Augustine, Florida, until his release in 1781. During his imprisonment, he wrote a parody of “God Save the King” which would be later known as “God Save the Thirteen States.”

After the war, Heyward contributed to rebuilding civic life in South Carolina. He helped found the South Carolina Agricultural Society and served as its first president in 1785. He retired from public life in 1799 and died on April 17, 1809, at the age of 63.

William Hooper (1742-1790)

William Hooper, born in June 1742 in Boston, Massachusetts, was a reluctant revolutionary. Raised by devoutly religious parents, his upbringing often placed him at odds with the growing revolutionary sentiment.

After attending Boston Latin School, Hooper graduated from Harvard in 1760. Though initially steered toward the clergy, he chose to pursue law. He later moved to North Carolina, married, and built a successful legal practice in Wilmington. In 1770, he was appointed deputy attorney general of North Carolina, defending Loyalist policies and British authority.

According to legend, Hooper was dragged through the streets of Hillsborough in 1770 by protesters angered over corrupt British rule—a sign of his loyalty to the Crown. Hooper even advised the British governor to stamp out rebellion.

Hooper’s views shifted after the Boston Port Act closed the harbor in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party. As a member of the North Carolina General Assembly, he began advocating for colonial rights, famously writing to a friend, “The Colonies are striding fast to independence, and ere long will build an empire upon the ruins of Great Britain…” Hooper was elected to the Continental Congress in 1774.

Nicknamed the “Prophet of Independence,” Hooper was among the first to foresee a complete break from Britain. During the war, his home was burned to the ground by the British, he was separated from his family for nearly a year, and he contracted malaria. After the war, Hooper resumed his law practice and advocated for fair treatment of British Loyalists. He died on October 14, 1790, at the age of 48.

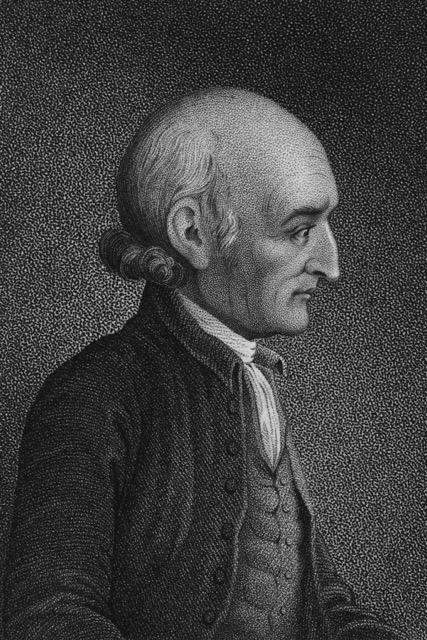

Stephen Hopkins (1707-1785)

Stephen Hopkins, born on March 7, 1707, in Providence, Rhode Island, was a leading figure of early American patriotism and a respected legal authority.

Though he had no formal education, Hopkins was a naturally gifted intellect who taught himself surveying and other practical sciences. A committed student from a young age, he began public service at 23 as a justice of the peace, quickly earning a reputation for competent leadership. He also became a successful merchant and amassed significant land holdings, expanding his influence in Rhode Island.

Before the Revolution, Hopkins rose through colonial government ranks, serving as justice, and later chief justice, of the Rhode Island Supreme Court by 1751.

As colonial governor, he supported British efforts during the French and Indian War while taking unorthodox positions for the time, notably advocating to ban the importation of slaves into Rhode Island.

He played a central role in the aftermath of the 1772 Gaspee Affair, in which colonists burned a British naval ship. Hopkins and other sympathetic officials helped ensure no colonists were indicted, shielding Patriots from British retaliation.

A vocal critic of British overreach, Hopkins was chosen as one of Rhode Island’s two delegates to the Continental Congress. Despite suffering from palsy, which caused his hand to tremble, he signed the Declaration of Independence at age 69, declaring, “My hand trembles, but my heart does not.”

Francis Hopkinson (1737-1791)

Francis Hopkinson was a musician, poet, artist, satirist, inventor, jurist, writer, and true Renaissance man of the American Revolution.

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Hopkinson was the eldest of eight children and the son of a prominent political leader. He graduated in the first class of the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania), studied law, and opened a legal practice in New Jersey. After marrying in 1768, he became a customs collector in New Castle, Delaware.

In 1776, Hopkinson represented New Jersey in the Continental Congress, and later held several government posts, including chairman of the Continental Navy Board, treasurer of loans, and judge of the admiralty court of Pennsylvania.

Hopkinson expressed his patriotism through music, satire, and poetry. His 1759 composition, “My Days Have Been So Wondrous Free,” is considered the first secular song by an American. He also authored “Temple of Minerva” in 1781, recognized as America’s first opera. Hopkinson was also a harpsichordist, church organist, and prolific essayist whose works supported the cause of independence.

In his allegorical piece “The New Roof,” Hopkinson described the Constitution as a structure that strengthened the weakened framework of the Articles of Confederation, portraying the founding generation as architects who saved the building.

Hopkinson is also credited by some historians with designing an early version of the American flag. He became one of the young nation’s best-known writers before his death in Philadelphia on May 9, 1791.

Samuel Huntington (1731-1796)

Samuel Huntington, born in July 1731 in Windham, Connecticut, was a lifelong public servant devoted to the cause of American independence. Raised on his family’s 180-acre farm, Huntington received his early education in local public schools and grew up in what would now be considered a middle-class household.

He initially apprenticed as a laborer making barrels and casks, but turned his interest toward law. Teaching himself with borrowed books, he was admitted to the bar at age 23 and earned such a strong reputation that he was appointed King’s Attorney for Connecticut.

Huntington’s political career advanced quickly. He served in the Connecticut Assembly and, by the mid-1770s, opposed British laws aimed at suppressing colonial resistance. He was elected to the Second Continental Congress, where he signed the Declaration of Independence and supported the Articles of Confederation.

From 1779 to 1781, he served as president of the Confederation Congress, the legislative body that governed the U.S. during the Revolutionary War. After the war, he returned to Connecticut, where he served on the state’s Supreme Court and as lieutenant governor.

In 1786, Huntington was elected governor of Connecticut, a role he held until his death in 1796. His administration focused on educational reform and opposing the slave trade.

Huntington died in office on January 5, 1796, at age 64, after almost a decade serving as governor. Though he and his wife, Martha, had no children, his legacy endures as one of service, integrity, and dedication to the founding of the nation.

Francis Lightfoot Lee (1734-1797)

Francis Lightfoot Lee was born on October 14, 1734, at Stratford Hall Plantation, Virginia, into the prominent Lee family, a political dynasty with roots in America dating back to the 1630s.

Raised on his father’s tobacco plantation, Lee was privately educated by tutors but did not attend college. As a young man, he focused on managing family landholdings, but by the late 1750s, he turned to politics. He was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he opposed British policies such as the Stamp Act and spoke out for colonial rights.

His dedication to the Patriot cause led to his election to both the First and Second Continental Congresses, where he served alongside his brother, Richard Henry Lee. Though equally committed to independence, the two brothers differed in style: Richard was known for his public speaking, while Francis was quieter and led through action rather than oratory.

In 1776, Francis Lightfoot Lee signed the Declaration of Independence. He also helped draft the Articles of Confederation and briefly served in the Virginia State Senate.

Following his public service, Lee retired to his estate, Menokin, where he lived a quieter life. He died on January 11, 1797, at age 62, just days after the death of his wife, Rebecca. The couple had no children.

Richard Henry Lee (1732-1794)

Richard Henry Lee, born on January 20, 1732, at Stratford Hall in Virginia, played an indispensable role for American independence. Over a long public life, he served in the Virginia House of Burgesses, as president of the Continental Congress, a U.S. Senator from Virginia, and as one of the first to hold the title of president pro tempore of the Senate.

Lee was educated at home before being sent to England at age 16 for formal schooling. He returned to Virginia in 1753 and soon entered public life, serving as a justice of the peace and later as a member of the House of Burgesses. Alongside figures like Patrick Henry, Lee became one of the earliest advocates for American independence, speaking out against British taxation policies.

As a delegate to the Continental Congress, Lee introduced the Lee Resolution, declaring that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States…” The resolution’s passage marked the formal break from British rule and set the stage for the adoption of the Declaration of Independence.

Lee remained active in national leadership after the war. From 1784 to 1785, he served as president of the Congress under the Articles of Confederation. In 1789, he was elected one of Virginia’s first U.S. Senators and briefly held the position of president pro tempore. He resigned in 1792 due to declining health.

Richard Henry Lee died on June 19, 1794, at the age of 62, at his estate in Chantilly, Virginia.

Francis Lewis (1713-1802)

Francis Lewis was a Welsh immigrant, merchant, prisoner of war, and supporter of American independence.

He was born in Llandaff, Wales, on March 21, 1713, and educated in Scotland and London. After inheriting his father’s estate at 21, he moved to the American colonies in 1734. Lewis’s mercantile business thrived in New York and Pennsylvania, and he was contracted by the British military to provide troops with uniforms during the French and Indian War.

In 1756, Lewis was captured by French forces and reportedly shipped to Europe in a crate. He spent seven years as a prisoner of war before being released in a prisoner exchange and returning to America.

Back in New York, Lewis resumed his business and received 5,000 acres from British authorities as compensation for his imprisonment. He became active in colonial politics, protesting the Stamp Act of 1765 and supporting the growing independence movement. In 1775, Lewis was elected to the Continental Congress. He signed the Declaration of Independence on August 2, 1776, after New York granted formal approval. During the war, he supplied the Continental Army with clothing, weapons, and provisions.

His home was later pillaged by British troops, and his wife, Elizabeth, was captured and held under harsh conditions. Though released in a prisoner exchange, she never recovered and died in 1779.

Following her death, Lewis withdrew from politics and spent his remaining years with his family. He died on December 31, 1802, at the age of 89.

Philip Livingston (1716-1778)

Philip Livingston, born on January 15, 1716, in Albany, New York, hailed from the wealthy and influential Livingston family. Philip spent his youth in opulent manor houses and townhomes before attending Yale College in the 1730s. After graduating, Philip settled in New York City and soon became one of the town’s most successful merchants. By the 1750s, Livingston entered public life, serving as an alderman and then elected representative within the British colonial government.

By the 1760s, British taxes designed to increase government revenue began to become unpopular with many American colonists. Livingston began to speak out publicly against these attempts at levying taxes on colonists without representation in Parliament. While resisting violent acts of protest, he attended the Stamp Act Congress of 1765.

Defeated for reelection in the colonial assembly by fierce British loyalists, Livingston was free to devote more of his time to the Patriot cause. In 1774, he was selected by members of his community to join the New York delegation in the First Continental Congress. Livingston was largely skeptical of American independence, his concerns of unprecedented levels of disorder often outweighing his desire to see British authority limited. He was not alone. The New York Assembly, under pressure to seek reconciliation, delayed in conveying their instructions to their delegates to the Continental Congress. When permission was finally received from New York, Livingston joined the rest of his colleagues and signed the Declaration of Independence one month late—on August 2, 1776.

Philip Livingston died of an illness two years later, at the age of 62. He left behind his wife, eight children, and a legacy of measured but steadfast patriotism.

Thomas Lynch Jr. (1749-1779)

Thomas Lynch Jr. was a scholar, legislator, farmer, soldier, and patriot who gave his life and family to the cause of American independence. He was the second-youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence and did not live to see the end of the Revolution.

Born on August 5, 1749, in Prince George’s Parish, South Carolina, Lynch was the son of a wealthy rice planter. He was educated in England, where he attended Eton College, Cambridge University, and later studied law at Middle Temple in London.

After returning to South Carolina, Lynch became a planter and married Elizabeth Shubrick. Following his father into revolutionary politics, he became a vocal advocate for independence and served in South Carolina’s first and second provincial congresses, helping draft the state’s first constitution.

He also served as a Captain in the South Carolina regiment, raising a company of troops before illness forced him to step down. While recovering, Lynch learned his father had suffered a severe stroke while serving in the Continental Congress. Lynch traveled to Philadelphia to assist and assume his father’s seat, making them the only father and son to serve concurrently in the Congress.

Lynch signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and reportedly left space on the parchment for his father, who died en route home.

Lynch’s health continued to decline, forcing him to withdraw from public life. In 1779, he and his wife sailed abroad seeking treatment but were never seen again—presumed lost in a shipwreck. He was 30 years old, the youngest signer of the Declaration to die.

Thomas McKean (1734-1817)

Thomas McKean was a lifelong public servant, statesman, and jurist who helped shape early American government.

He was born on March 19, 1734, in Chester County, Pennsylvania, the son of an innkeeper and farmer. Though a Pennsylvanian by birth, McKean studied and practiced law in Delaware, where he held a number of public offices, including deputy attorney general, justice of the peace, and speaker of the colonial assembly.

In 1765, McKean represented Delaware at the Stamp Act Congress, opposing British economic policies. He later helped dissolve British control in Delaware and was elected to the Continental Congress, where he, along with Caesar Rodney, ensured Delaware supported independence.

McKean uniquely held office in both Delaware and Pennsylvania simultaneously and contributed to both states’ constitutions. In 1777, he became Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, serving for 22 years.

He also served as a colonel during the Revolutionary War, became President of the Continental Congress, and signed the Articles of Confederation. After the war, McKean helped secure Pennsylvania’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution. As a judge, he supported the principle of judicial review well before it was nationally established.

McKean later served three terms as governor of Pennsylvania, surviving political opposition and an attempted impeachment. At age 80, he helped organize a citizens group to defend Philadelphia during the War of 1812.

Thomas McKean died of natural causes in 1817.

Arthur Middleton (1742-1787)

Arthur Middleton was a South Carolinian patriot who fiercely defended his colony’s interests and supported radical measures against British rule. He was one of a handful of signers of the Declaration of Independence to become a prisoner of war.

Born on June 26, 1742, near Charleston, South Carolina, Middleton was the son of a powerful plantation owner who later served in the Continental Congress. At age 12, Middleton began his education in England, graduating from St. John’s College (Cambridge) and studying law at Middle Temple in London.

After returning to South Carolina, he managed a rice plantation, became a Justice of the Peace, and served in the provincial House of Commons. By 1775, Middleton was a strong critic of British authority, advocating for harsh measures against Loyalists and helping to organize military defense as part of the Council of Safety. He contributed to drafting South Carolina’s constitution and co-designed the state’s official seal.

When his father became ill, Middleton replaced him in the Continental Congress, where he signed the Declaration of Independence and supported additional military aid to the South. He later returned to South Carolina and fought in the Battle of Charleston, where he was captured by British forces and held for a year.

After his release, Middleton rejoined the Continental Congress, where he strongly advocated for punitive actions against British military leaders, including Lord Cornwallis. Following the war, he rebuilt his damaged plantation, served in the state legislature, and became a trustee of the College of Charleston.

Lewis Morris (1726-1798)

Born in Westchester County, New York, Lewis Morris attended Yale College. He married Mary Walton and they had ten children together.

As the eldest son, Morris acquired his father’s estate at Morrisania, New York. Having acquired properties in New York and New Jersey, Morris grew increasingly frustrated with British control over trade policies in the colonies, and eventually became a fierce proponent of independence.

In 1775, Morris was elected to the Second Continental Congress, and from there was sent to the western country to persuade the Indians not to join the British cause.

While the movement for independence grew throughout the colonies, the provincial congress of New York was reluctant to endorse the cause wholeheartedly. Yet, Morris held firm in his ardent fervor for independence. It wasn’t until after all other colonies reached a consensus for independence that the New York delegation fully supported the cause. Lewis Morris proudly added his signature to the Declaration of Independence.

In addition to founding father, Morris carried many other titles: Judge of Westchester County, Senator in New York, Major General in the Westchester County Militia, member of New York’s first Board of Regents of the University of New York, and delegate to the State Convention that ratified the Federal Constitution in 1788.

During his time in the political sphere of influence, Morris fought to better public education across New York, and supported improved transportation systems for the sake of interstate commerce. He passed away at his beloved Morrisania at age 71.

Robert Morris (1734-1806)

Known as “Financier of the Revolution,” Robert Morris was indispensable to the cause of American Independence—using his commercial and financial brilliance to almost single-handedly propel American war efforts through to final victory.

In January of 1734, Morris was born in Liverpool, England. His father was a successful businessman, with extensive ties to the colonies, and brought Robert, at 13, to America.

Soon after, tragedy struck, and Morris was left virtually an orphan—though he would go on to form the Willing, Morris & Co., one of Philadelphia’s most successful merchant houses.

In 1775, Morris entered public service, elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly and chosen as a Delegate to the Second Continental Congress, where he served on a number of committees.

At the start of the Revolution, he was considered the richest man in America. He worked closely with General George Washington to secure supplies, and often extended his own personal credit or borrowed from friends.

John Morton (1725-1777)

John Morton was the first of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence to die, passing away less than a year after casting a pivotal vote that changed the course of history.

Born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in 1725, Morton’s father died before he was born. He was raised by his mother and stepfather and was largely self-taught. He began his career as a surveyor while tending the family farm.

In 1756, Morton was elected to the Pennsylvania General Assembly. Over 19 terms, he helped write 72 bills, 50 of which became law. In 1775, he was unanimously elected Speaker of the Assembly. He also held various public roles, including justice of the peace, sheriff, road commissioner, delegate to the Stamp Act Congress in 1765, and associate justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

Morton served in both the First and Second Continental Congresses and contributed to drafting the Articles of Confederation, which were ratified after his death. His most consequential act came in July of 1776, when, among Pennsylvania’s seven delegates, two voted no, two abstained, and two voted yes. Morton cast the deciding vote for independence, securing Pennsylvania’s support.

He died in the spring of 1777 at the age of 51 from tuberculosis. Facing criticism for his vote, Morton’s final message to his detractors was: “Tell them they shall live to see the hour when they shall acknowledge it to have been the most glorious service I ever rendered to my country.”

Thomas Nelson Jr. (1738-1789)

Founding Father Thomas Nelson Jr. was born in 1738 in Yorktown to one of Virginia’s First Families. He grew up in all the trappings of wealth and prepared for taking his eventual place as a top businessman and leader.

In 1761, Nelson entered public service, elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses. When the patriots issued a resolution excoriating British Parliament’s “Boston Port Bill,” Nelson sided with the colonists against the Royal Governor, who dissolved the assembly. This event set in motion the cause for independence.

Nelson was elected to the Virginia Convention of 1774 and 1775, and in the latter nudged the members toward action—proposing organizing a militia in the Commonwealth.

Between 1775 and 1777, Nelson served in the Continental Congress, proudly supporting the cause of Independence.

In 1781, Nelson was elected to replace Thomas Jefferson as Governor. To repel the British invasion, the legislature granted him robust powers to effectively defend Virginia. As Brigadier General, he raised volunteer troops. He led militia forces. Alongside Washington and Rochambeau, he besieged the British in his hometown, Yorktown. According to family tradition, Nelson told Washington to aim fire on his home when he heard it was occupied by the British.

Nelson was among the signers of the Declaration to make good on his pledge to give his fortune to the cause of Independence. He died poor in 1789, leaving behind his wife and 11 children.

William Paca (1740-1799)

A respected lawyer, jurist, and public servant, William Paca was known for his quiet, razor-sharp logic and strategy—and his impact on Maryland politics before, during, and after the War for Independence.

Born in 1740 near Abingdon, Maryland to a wealthy planter, Paca later attended Philadelphia College—today the University of Pennsylvania. Upon graduation, he studied law in Annapolis. In 1761, Paca began practicing law in local courts. As British oppression against the colonies grew, he helped form the “Sons of Liberty,” and in 1767, aligning himself with the party resisting the British Stamp Act, was elected to the Lower House of the Maryland Assembly.

Later, Paca organized local committees to oppose the Boston Port Act—the first in a series of “Intolerable Acts,” which closed the Boston port and ordered the city to pay a large fine for the Boston Tea Party. Paca was sent as a Delegate to the First Continental Congress, where he helped craft resolutions and petitions. While the Maryland Convention – still loyal to the crown as late as June 1776—initially barred Paca from voting for independence, they reversed course by July, and Paca proudly voted in the affirmative.

During the war, Paca served on Congress’ newly created Court of Appeals. In 1782, he became Governor and he was an early advocate of supporting veterans returning from war. In 1786, as a Maryland House Delegate, Paca became a leader of the Antifederalist movement. His primary objections to the Constitution– that there were inadequate safeguards for freedom of religion, press, and legal protection for those accused of crimes – were later incorporated into the Bill of Rights.

For the last ten years of his life, Paca served on the Federal District Court for Maryland until his death in 1799.

Robert Treat Paine (1731-1814)

Of the four signers from Massachusetts, Robert Treat Paine is lesser known today than John Hancock, John Adams, and Samuel Adams, yet he left a lasting mark on the founding of the United States.

Born on March 11, 1731, in Boston, Massachusetts, Paine was the son of a pastor-turned-merchant and descended from Mayflower settler Stephen Hopkins. He entered Harvard College at 14, graduating at 18, and pursued various careers—including teaching, preaching, and even whaling in Greenland—before turning to law. In 1761, he moved to Taunton and became a respected attorney.

Paine’s legal prominence grew alongside his rival, John Adams. In 1770, the two faced off in the Boston Massacre trial, where Paine prosecuted British soldiers and Adams served as defense counsel. After six days in court, Paine lost the case.

Despite the loss, his performance earned him widespread recognition. In 1774, Paine was elected to the Continental Congress, and in 1776, he signed the Declaration of Independence.

Shortly thereafter, Paine was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, where he served as Speaker and helped draft the state constitution. He became the state’s first Attorney General, notably prosecuting Shays’ Rebellion, and from 1790 to 1804, served as a Massachusetts Supreme Court Justice.

Late in life, Paine co-founded the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He died in 1814, at the age of 83, and was buried in Boston’s Granary Burying Ground, also the resting place of the Boston Massacre victims.

John Penn (1741-1788)

John Penn, born May 17, 1741, in Caroline County, Virginia, emerged from an upbringing of little formal education to eventually become one of just 56 men to etch his name on the Declaration of Independence.

After his father died in 1759, Penn discovered a newfound motivation to educate himself and through the aid of his uncle pursued legal studies. In 1762, Penn became licensed to practice law in Virginia, where he worked until the cause of the American Revolution called him to enter public life.

After moving to North Carolina, Penn’s fiery opposition to the Stamp Act ignited his political ascent. By 1775, Penn was on his way to the Second Continental Congress. Upon his arrival, Penn declared, “My first wish is for America to be free.”

In Philadelphia, Penn’s uncompromising passion sparked clashes with his colleagues, notably Continental Congress President Henry Laurens. According to some historians, the two men nearly dueled in a vacant Philadelphia lot, but decided to make peace on the way there.

Penn signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation, making his name one of 16 that both documents bear. Later, as one of three men on the Board of War for North Carolina, Penn bolstered General Nathaniel Greene against the weakening Cornwallis campaign, forcing the British retreat through North Carolina to Yorktown that won the war.

When America needed Penn most, no sacrifice was too great for independence.

George Read (1733-1798)

George Read, born on September 18, 1733, in Cecil County, Maryland, was a self-made lawyer and patriot who helped shape the foundation of American government. He studied law at an early age and, by 21, established a legal practice in Delaware, quickly becoming one of the colony’s most respected attorneys.

In 1763, at 29, Read was appointed Attorney General for Lower Delaware by the British Crown, a position he held for over a decade. Though loyal to the law, Read hoped to resolve colonial grievances without war and initially sought reconciliation with Britain.

In 1774, Read left his post to join the Continental Congress, continuing to advocate for compromise. However, as the push for independence became unavoidable, he signed the Declaration of Independence. In retaliation, British forces ransacked his home and captured his wife.

Recognized for his contributions, Read was selected to draft Delaware’s first constitution, and is considered by some to be “the father” of Delaware. In 1777, he served as acting governor when the British captured his predecessor. A decade later, Read led Delaware’s delegation at the Constitutional Convention, where he strongly supported small state interests. After securing those rights, he urged Delaware to become the first state to ratify the U.S. Constitution.

Read continued his public service as a U.S. Senator and later as Chief Justice of Delaware, a role he held until his death on September 21, 1798.

Caesar Rodney (1728-1784)

Caesar Rodney was born October 7, 1728 on a sprawling farm in Kent County, Delaware. After losing his father in his youth, Rodney inherited wealth and responsibility that he used for the good of the new nation.

At 27, Rodney was commissioned High Sheriff of Kent County Delaware, and he served as an officer in the French and Indian War. Among the many public offices he held, Rodney later joined the Stamp Act Congress and the Continental Congress. No Delawarean since has matched the sheer number of positions held by Rodney and the rigor of his public life. His defining moment came on July 1, 1776, when, despite battling asthma and a disfiguring facial cancer, Rodney rode 80 miles through a thunderstorm and the dead of night from Dover to Philadelphia. Arriving at Independence Hall on July 2nd, spurs clinking, he broke Delaware’s deadlock, casting the decisive vote for the Declaration of Independence. It was an act of duty, courage, and treason that cemented his patriotic legacy.

As wartime governor and major-general, Rodney led Delaware’s militia and supported Washington’s Continental Army with all the money, supplies, and manpower his state could muster. At a low moment for the Revolutionary cause, he secured military equipment with money from his own pocket. Later, the Continental Congress elected him President of Delaware in 1778, a position he used to stabilize the state’s war-torn finances and politics.

As the War came to a close, Rodney’s health deteriorated under the strain of cancer. He became too ill to remain in political life, but as a final gesture of respect for Rodney’s honorable service to Delaware, the 1783-1784 Legislative Council elected him as Speaker. He died on June 26, 1784, leaving behind no children, but rather, a nation shaped by his sacrifice.

George Ross (1730-1779)

Born in New Castle, Delaware, George Ross was raised in a very large family. He received a classical education at home before studying law in Philadelphia under his brother, John Ross. In 1750, at 20 years old, he was admitted to the bar and established a successful legal practice in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where his intellect and eloquence earned him a reputation as a skilled attorney.

Ross’ political and governmental career began in the 1750s when he was chosen to represent the crown of England as the King’s prosecutor in Pennsylvania. In 1768, he was elected to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly. Initially a moderate, he leaned toward reconciliation with Britain but grew increasingly supportive of colonial rights as tensions escalated.

By 1774, he was a delegate to the First Continental Congress, advocating for unified colonial resistance. His legal acumen and commitment to liberty made him a key figure in drafting petitions and resolutions. In 1776, as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Ross proudly signed the Declaration of Independence.

A staunch patriot, Ross served on Pennsylvania’s Committee of Safety, organizing defenses during the Revolutionary War. He also held the rank of colonel in the Pennsylvania militia, contributing to the war effort despite health challenges. In 1779, Ross was appointed to the Pennsylvania Court of Admiralty, but his judicial tenure was brief. Stricken by gout, he died later that year at age 49, leaving behind his wife, Ann Lawler, and three children.

Ross’s legal expertise and dedication to the patriot cause helped shape the fledgling nation.

Dr. Benjamin Rush (1746-1813)

A Physician, an abolitionist, and an early adopter of the cause for independence, Dr. Benjamin Rush was one of the most influential founding fathers. Born on January 4, 1746, in Byberry Pennsylvania, Rush was raised in a pious Presbyterian family and was educated at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton) where he graduated in 1760 at the age of 14. He pursued medicine, apprenticing in Philadelphia and earning his medical degree from the University of Edinburgh in 1768. He returned to Philadelphia in 1769 and established a medical practice. That same year, he became a professor of chemistry at the College of Philadelphia, and in 1770 he published America’s first chemistry textbook. Rush’s medical contributions were groundbreaking, albeit controversial. He pioneered American psychiatric mental health treatment and is often referred to as the “father of American psychiatry.” Following the Revolutionary War, Rush opened the United States’ first free medical clinic, the Philadelphia Dispensary.

Rush was also an early advocate for the education of women and the abolition of slavery. A steadfast patriot, Rush joined the Sons of Liberty and influenced Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, a pivotal pro-independence pamphlet. He was elected to the Continental Congress in 1776 and signed the Declaration of Independence as a representative of Pennsylvania.Rush was not reelected that following year, due to his opposition to the Pennsylvania state constitution, and subsequently accepted the position of Surgeon General in the Middle Department of the Continental Army. Rush was highly critical of the conditions in which soldiers were being treated and angrily resigned his post in 1778. He briefly supported efforts to remove General George Washington from his post, a stance that cost Rush considerable social and political capital.

However, largely due to his medical and civic contributions, Rush continued to play an important role in American politics. Appointed treasurer of the U.S. Mint by President John Adams, Rush also helped achieve the historic reconciliation between Adams and Thomas Jefferson.

Edward Rutledge (1749-1800)

Edward Rutledge, born in Charleston, South Carolina, was the youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence. The son of Dr. John Rutledge, an Irish immigrant and physician, and Sarah Hext, a wealthy South Carolinian, Rutledge grew up in an aristocratic family.

Rutledge studied law in England and was admitted to the English Bar in 1772 before returning to Charleston, where he established a thriving legal practice. In 1774, he married the sister of Arthur Middleton, a fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Rutledge’s political career began in 1774 when, at the age of 24, he was elected to the first Continental Congress to represent South Carolina alongside his brother John.

Initially, Rutledge favored reconciliation with Britain. However, he ultimately supported the Declaration of Independence, reportedly persuading the South Carolina delegation to vote in the affirmative.

A proud American patriot, Rutledge served as a captain in the Charleston Artillery Battalion during the Revolutionary War. He was captured by the British during the 1780 Siege of Charleston and was imprisoned until a prisoner exchange in July 1781.

After the war, Rutledge returned home to South Carolina, serving in the state legislature from 1782-1798. Here Rutledge fought against opening the African slave trade and voted to ratify the U.S. Constitution.

Elected governor in 1798, Rutledge died in office at the age of 50.

Roger Sherman (1721-1793)

Roger Sherman, born on April 19, 1721, in Newton, Massachusetts, was the only person to have signed all four of the most significant documents in our nation’s early history: the Continental Association from the first Continental Congress, the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the United States Constitution.

The son of a farmer and cobbler, Sherman received minimal education. Nevertheless, he was an avid learner who made extensive use of his father’s sizable personal library. In 1743, Sherman moved to New Milford, Connecticut. There, he worked as a surveyor and storekeeper. He was admitted to the bar in 1754, despite having no formal legal training, and began his legal career.

Sherman entered politics in 1755 as justice of the peace and a member of Connecticut’s General Assembly. During the Second Continental Congress, Sherman was appointed to the Committee of Five where he helped review and refine Thomas Jefferson’s drafts of the Declaration of Independence.

Following America’s War for Independence, Sherman participated in the Constitutional Convention and proposed the Great Compromise (also known as the “Connecticut Compromise”), establishing a bicameral legislature with equal state representation in the Senate and population-based representation in the House.

In 1784, Sherman was elected as the mayor of New Haven, Connecticut and held this position concurrently alongside others until his death. Sherman was elected to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1789. In 1791, he was chosen to fill a vacancy in the U.S. Senate. Two years later, he fell ill with typhoid fever and died.

James Smith (1719-1806)

James Smith was born in Ireland around 1719. His family fled the landlords of the Old World for the freedom of Pennsylvania around 1727, settling as farmers on the Susquehanna in Chester County.

Receiving a classical education from a local minister, Smith continued his studies in classics, adding land surveying, at the Philadelphia Academy, now known as the University of Pennsylvania.

Admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar in 1745, Smith became a prominent man of the law and business, at one point founding an iron manufacturing company and soon emerging as a leader in Pennsylvania politics.

In 1774, Smith helped form and organize the state’s support for the cause of independence as he raised a volunteer company of militia.

Smith was appointed to the provincial convention in Philadelphia in 1775 where he declared, “If the British administration should determine by force to effect a submission to the late arbitrary acts of the British parliament, in such a situation, we hold it our indispensable duty to resist such force, and at every hazard to defend the rights and liberties of America.” He was then elected to the Second Continental Congress. He represented Pennsylvania in the Congress until 1778, going on to serve a term in the State Assembly, as a judge of the state High Court of Appeals, and as Brigadier General of the Pennsylvania militia in 1781.

He died on July 11, 1806, in York, Pennsylvania at the age of 87. A fire destroyed his office and papers shortly before his death, contributing to his relative obscurity.

Richard Stockton (1730-1781)

Richard Stockton was born on October 1, 1730, in Princeton, New Jersey. He earned a Bachelor of Arts from the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University, completed a legal apprenticeship, and was admitted to the bar in 1754.

In 1755, Stockton married the poet Annis Boudinot, with whom he had six children. His son Richard would go on to become a Representative and Senator, and he was father-in-law to Benjamin Rush.

Stockton achieved prominence as a lawyer, and was appointed to the New Jersey Executive Council in 1768, and later to the colony’s Supreme Court in 1774. Stockton served as a trustee of the college for 24 years and helped secure the Princeton presidency of the Rev. John Witherspoon.

The Stamp Act crisis of 1765 led him to question Parliament’s control over the colonies, and by 1774, he advocated for colonial self-rule under the Crown. Though known as a moderate, his dedication to the cause of American independence intensified, and he was elected to the Second Continental Congress in 1776.

In November 1776, while attempting to evacuate his family from Princeton, he was captured by British forces at Perth Amboy, New Jersey, and imprisoned in New York. Treated with inhumane severity, he was released in the early days of 1777 in poor health to discover British troops had occupied and partially burned his home. He died of cancer on February 28, 1781, at the age of 50.

Thomas Stone (1743-1787)

Thomas Stone was born in 1743, in Charles County, Maryland, to a wealthy planter family. After completing preparatory studies in classics, he pursued law in Annapolis under Thomas Johnson, who would become Maryland’s first state governor.

Admitted to the Maryland bar in 1764, Stone opened a practice in Frederick, Maryland. His political career began in 1774, when he was elected from Charles County to the first Maryland Convention.Stone was initially cautious on the question of independence, even as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, expressing in April 1776 his “wish to conduct affairs so that a just and honorable reconciliation should take place, or that we should be pretty unanimous in a resolution to fight it out for Independence. The proper way to effect this is not to move too quick.”

Of course, a near unanimous “resolution to fight” did pass, and Stone signed his name for the cause of Independence. He then served as a Maryland state senator. While in the Congress, he was a member of the committee that framed the Articles of Confederation in 1777.

In 1787, he was elected to attend the Constitutional Convention, but declined due to his wife’s failing health. Margaret Stone died in June that year, and Stone soon followed on October 5, 1787, in Alexandria, Virginia, at the age of 44, succumbing to what many believed was a devastating heartbreak.

George Taylor (1716-1781)

George Taylor was born in 1716 in Ireland. He immigrated to Pennsylvania in 1736, where he worked as an iron worker for Samuel Nutt at Coventry Forge near Philadelphia.

Nutt died in 1737 and by 1743, Taylor was managing the iron furnace and married to Ann Taylor Savage. Ann died in 1768, and Taylor later had a relationship with Naomi Smith, his housekeeper, with whom he had five children out of wedlock.

Taylor’s political career began in 1747 when he was commissioned captain in the Chester County militia. He served as a justice of the peace when he moved to Easton, Pennsylvania, a member of the provincial assembly, and a judge of the county court. His ironworks, which remained his chief business, became vital during the Revolution, casting grapeshot, cannonballs, bar shot, and cannon for the Continental Army.

In July 1776, Taylor was one of several selected as representatives to the Continental Congress to replace members that had refused to sign the Declaration of Independence; he appended his signature to the document on August 2, 1776.

In March 1777, he was elected to the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, but served only six weeks before retiring due to illness and financial straits. Taylor died on February 23, 1781, at the age of 65.

Matthew Thornton (1714-1803)

Matthew Thornton was born in Ireland in 1714 and moved to what would become Maine as a child. At age eight, his family fled an Indian attack, escaping by canoe to Casco Bay, and later settled in Worcester, Massachusetts. Thornton received a classical education at Worcester Academy, studied medicine, and began a successful practice in Londonderry, New Hampshire in 1740.

In 1745, he served as a surgeon for the New Hampshire militia during King George’s War. During the Battle of Louisburg, he earned a reputation as an excellent doctor by losing only six men to sickness. This led to his election in 1758 to the colonial legislature, where he became a vocal critic of British Parliament.

Following the Battle of Lexington and Concord in 1775, Governor Wentworth fled New Hampshire, and Thornton was named President of the New Hampshire Provincial Congress. In that role, he urged citizens to take up arms, citing British cruelty and civilian suffering.

Thornton led the committee to draft a new state constitution, chaired the Council of Safety, and served in both the Upper and Lower houses of the legislature.

In September 1776, Thornton was appointed a delegate to the Continental Congress. Officially seated on November 4, he became one of the last signers of the Declaration of Independence. Though late, he insisted on being added to the list, wanting the “same privilege as the others… to be hanged for his patriotism.”

In 1777, he left Congress and resumed his earlier role on the New Hampshire Superior Court. Thornton died in 1803, at approximately 89 years old. His original gravestone bore the inscription: “An Honest Man.”

George Walton (1741-1804)

George Walton was born in Virginia and orphaned as a young child. Raised by an uncle with thirteen children, Walton taught himself by firelight at night while apprenticing as a carpenter. In 1769, he moved to Savannah, Georgia, where he studied law and joined the bar in 1774.