Apples to Äpfel: Recent Inflation Trends in the G7

In May, Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation in the United States was four percent year-on-year. Inflation in the U.S. has declined substantially since last summer, when its yearly growth peaked at over nine percent. One common question this raises is how U.S. inflation compares to inflation in other advanced countries. Due to a variety of measurement issues, such a comparison is harder than is commonly recognized.

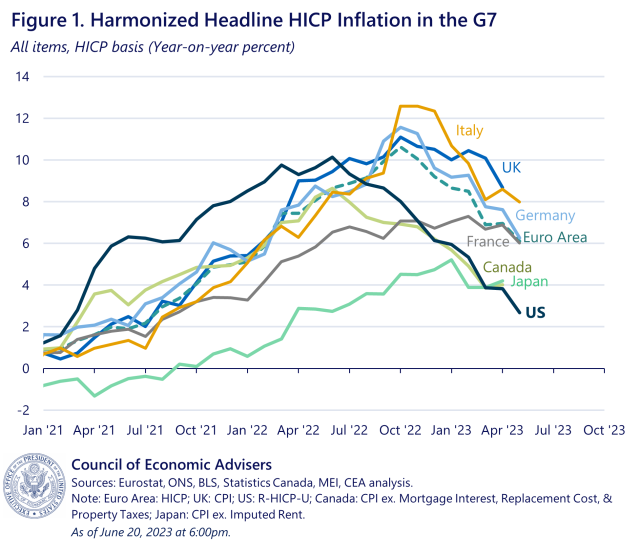

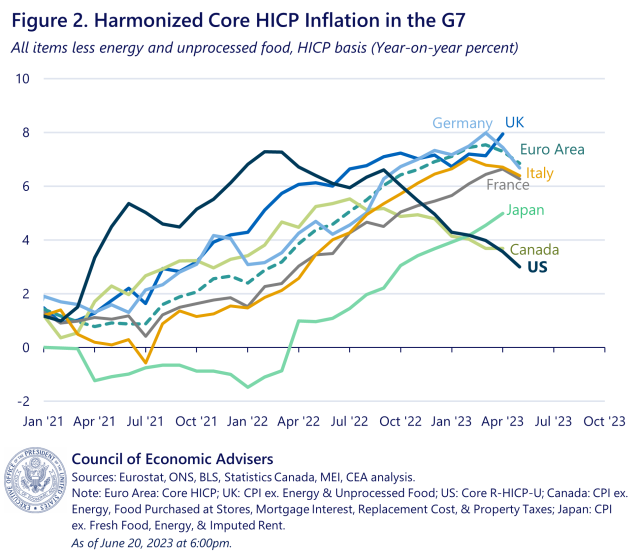

In this blog post, the Council of Economic Advisers assembles and constructs harmonized inflation data for G7 countries, allowing for more apples-to-apples inflation comparisons. U.S. harmonized inflation generally rose and peaked earlier in the pandemic than the rest of the G7, measured on a 12-month basis. Though inflation remains elevated across all countries in this analysis, the U.S. now has the lowest 12-month harmonized inflation in the G7, both for overall and core inflation. That said, inflation going forward remains considerably uncertain across all G7 nations, including the U.S.

Inflation measurement can differ significantly between countries.

Measuring inflation is a difficult but crucial task for national statistical agencies and doing so raises a host of methodological choices—and challenges. While advanced countries address many of these hurdles in similar ways, it is little surprise that methodological differences both large and small have also arisen over time.

One of the most significant methodological differences involves owner-occupied housing. In the U.S., for example, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) includes owners’ equivalent rent (OER)—the rental value of housing services received by homeowners—as a part of CPI. BLS bases this, in part, on estimates of the expected market rate rent for each owner-occupied unit given its amenities and characteristics. Statistics Canada also incorporates owner-occupied housing into Canada’s CPI, but it uses a substantially different approach, pricing mortgage interest costs and housing replacement costs instead of owner’s equivalent rent. To widen the differences even further: in Europe, Eurostat excludes owner-occupied housing rents entirely from the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP).

These methodological differences have real, non-trivial implications: owner-occupied housing can make up a significant share of the consumer price basket (e.g. 1/5 in the U.S. CPI), and in the U.S., housing has been one of the primary drivers of recent inflation. Therefore, it is not only a question of whether or not owner-occupied housing is included, but how it is measured that matters significantly when comparing inflation across national borders.

Differences arise elsewhere, too. Economists and policymakers often track “core” inflation—inflation excluding volatile food and energy prices—because it tends to be a better predictor of future overall inflation than current “headline” inflation itself. But the precise definition of “core” varies by country. In the U.S., core CPI excludes both food at home (groceries) and food away from home (restaurants), while Japan only excludes “fresh food” from its core CPI (essentially groceries). Likewise, in Europe, the Eurostat measure core HICP only excludes “unprocessed foods” (also essentially groceries), but, confusingly, the core measure used by the European Central Bank excludes both groceries and restaurant food prices as well as alcohol and tobacco. These different definitions further obscure international comparisons.

According to common inflation definitions, U.S. inflation generally peaked earlier and is now lower than the rest of the G7.

Figures 1 and 2 harmonize headline and core inflation, respectively, among the G7 countries using a common European HICP definition.[1] Put simply, “harmonizing” means using the same consumer basket in all countries. Both figures exclude the direct costs of owner-occupied housing (owners’ equivalent rent or, in the case of Canada, mortgage interest, replacement costs, and property taxes), but still include rental costs and the repair costs of owner-occupied housing. Furthermore, core also excludes unprocessed foods (or their equivalent) and energy goods and services, but includes prices at restaurants. BLS helpfully produces a U.S. inflation series—the R-HICP-U—that already makes all of these adjustments. For Canada and Japan, the CEA uses their national CPIs and strips out these categories. The result is close to a truly apples-to-apples inflation concept that allows for international comparisons, despite lacking some components with which many American inflation analysts are familiar.

Importantly, BLS’s methodology of incorporating owner-equivalent rent is widely-acknowledged by economists as the approach most consistent with CPI’s explicit goal of measuring consumption prices over time. The HICP approach outlined here should absolutely not be interpreted as “better,” “more accurate,” or “right.” Rather, this approach is necessary to fairly compare U.S. inflation with that of other advanced economies.

The CEA’s series shows that harmonized inflation in the U.S. rose earlier, and peaked earlier, than it did in other G7 nations (with the exception of Canada where headline inflation peaked the same month as the U.S.). Furthermore, the U.S. is now seeing lower inflation than the other G7 nations. Part of this result is due to the omission of owner-occupied housing costs. Of course, another important factor for headline inflation is the war in Ukraine, which has affected food and energy prices globally but especially in Europe, which has had the broadest exposure to the consequences of the conflict. Still, differences in sensitivity to the Ukraine conflict cannot explain all of the cross-country variation. When looking at core harmonized inflation on a 12-month basis, which strips out the energy and grocery costs most pinched by the war, U.S. inflation is still below other G7 countries, including Japan. In fact, both Germany and the UK saw higher core harmonized inflation in April than the U.S.’s early-2022 peak.

Effectively comparing inflation across countries requires shared definitions. The CEA’s harmonized measure produces a fair calculation and ultimately shows that while there were common pandemic experiences across advanced G7 countries, there was a great deal of variation in experiences, too. The CEA’s series also reveals that both headline and core U.S. inflation is growing more slowly compared to other G7 countries. Going forward, the near-term evolution of inflation remains considerably uncertain.

[1] Harmonizing instead to a U.S. definition is impossible given the lack of consistent imputed rental estimates across Europe and Canada.