The June Consumer Price Index: Disinflation, Deflation, and Buying Power in the U.S. Economy

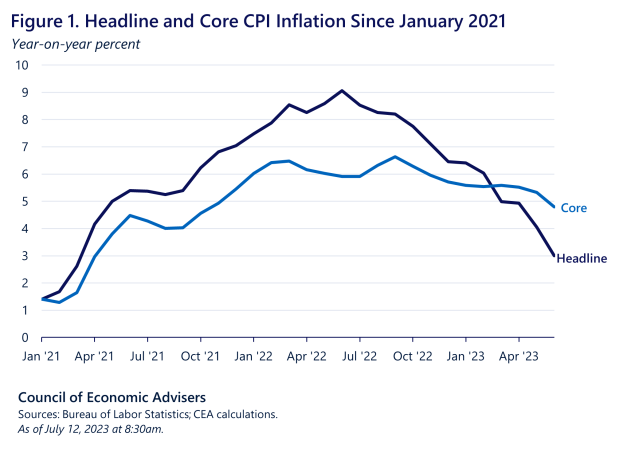

Today we learned that overall consumer prices as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), “headline” inflation, grew 0.2 percent in June, below market expectations and higher than May’s 0.1 percent rate. “Core” inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, also grew by 0.2 percent, also below market expectations and below May’s 0.4 percent. Since monthly data can be noisy and obscure underlying trends, economists often look at inflation over longer periods as well. Over the last 12 months, headline inflation was 3.0 percent, while core was 4.8 percent.

While inflation remains elevated, the U.S. has made meaningful progress in reducing it since last year, especially headline inflation, which is down over two-thirds since last June (from 9.1 to 3 percent). There are three ways households experience relief from high inflation: disinflation (slower inflation), deflation (falling prices), and real wage gains. As this post shows, from the perspective of overall inflation (as opposed to core inflation, which omits food and energy prices), all three are in play in the current economy.

Disinflation means slower inflation over time. The U.S. has now seen 12 straight months of disinflation in the annual headline CPI inflation measure. Core inflation has come down much less, but it too has undergone some disinflation, having peaked at 6.6 percent in September 2022.

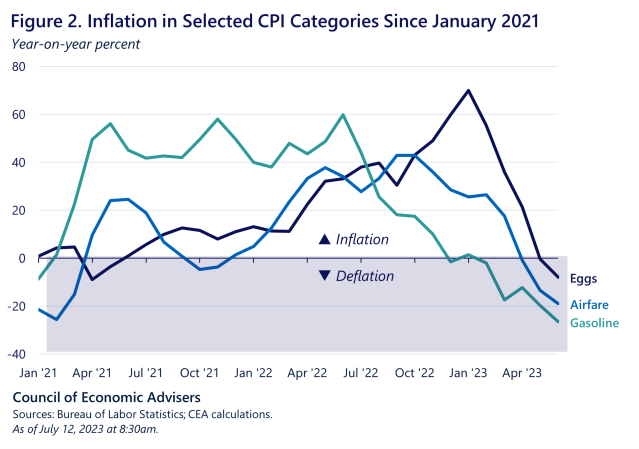

However, when people talk about relief from inflation, they often mean lower prices levels. That is, deflation, or negative inflation. Some goods and services tracked by the CPI have experienced deflation in past year, such as retail gasoline or eggs, whose prices are down by -26.5and -7.9percent, respectively.

Both disinflation and deflation provide relief from inflation. Deflation in specific products like eggs, for which prices had previously spiked up due to an economic shock (an avian flu outbreak last year) and then renormalized, is not uncommon. Pervasive deflation across many different goods and services, however, is a rare phenomenon in advanced economies and it is usually a sign of dangerously weak growth.

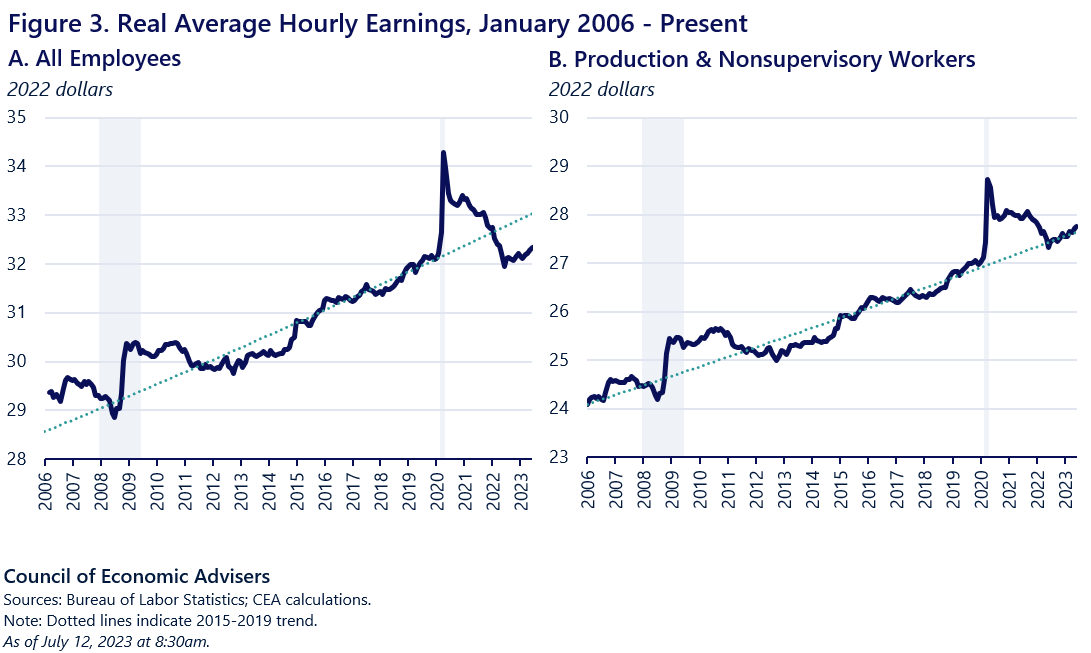

If prices are broadly rising, even in normal times, how can households improve their buying power over time? The answer is higher wages and incomes. Leaving out the pandemic, which had a highly unusual impact on most economic variables, nominal (that is, not adjusted for inflation) wages for middle-wage workers—the 80 percent of workers who are blue collar in manufacturing and non-managers in services (called “production and nonsupervisory workers” by BLS)—grew in 94 percent of the months from 1990 through 2019. When nominal wage growth outpaces inflation, economists call that real wage growth, meaning the buying power of paychecks is rising, on average.

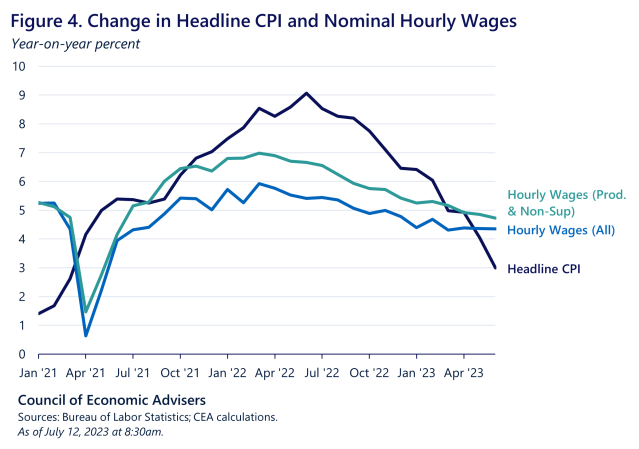

In recent months, the U.S. economy has seen each of these phenomena: disinflation, deflation, and real wage growth. Figure 1 shows clear disinflation in the headline CPI, though considerably less so in the core. Figure 2 shows a few examples of deflation in highly visible prices, including retail gas, eggs, and airline fares. Figure 3 shows that the real wage of all private workers is above its prepandemic level while that of middle-wage workers is back to its prepandemic trend. Figure 4 shows nominal wage growth and inflation separately, illustrating that even though nominal wage growth has cooled somewhat, real wages have made gains because of the magnitude of recent disinflation.

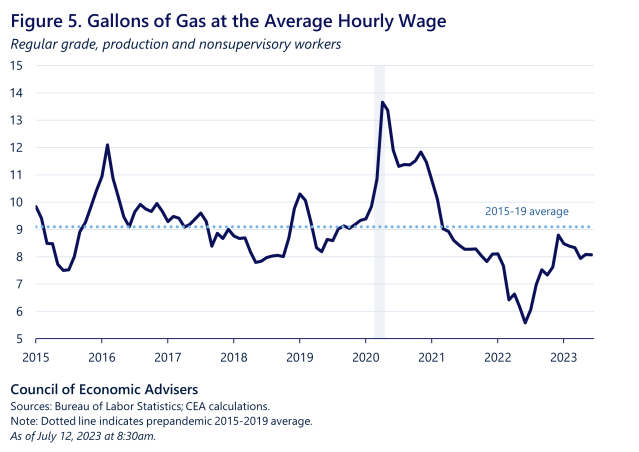

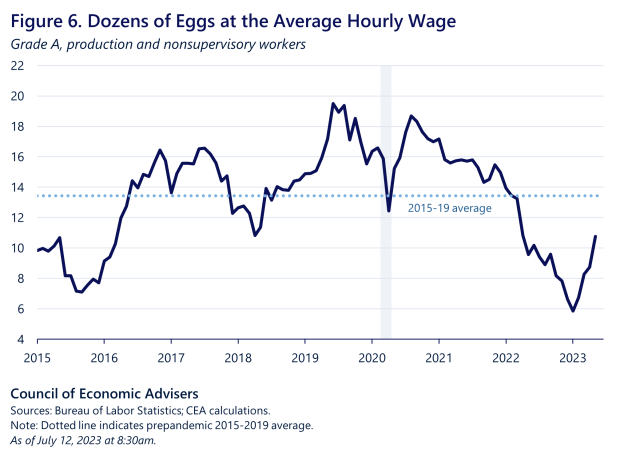

Gasoline prices provide an example into how these trends can reinforce each other. Figure 5 shows the number of gallons of gas that one could purchase with one hour of work at the average wage (a higher number is better because it means more buying power for the average worker). As nominal pay has gone up over the past year, gas prices have fallen. The result is that a year ago, an hour of work paid for about 5.5 gallons of gas; in June, it paid for 8 gallons, an increase of 45 percent. Figure 6 shows a similar calculation for a dozen eggs, where purchasing power has also been rising to more normal levels as wages grow and avian flu subsides.

Should these broad trends of rising nominal wages and easing inflation continue, then by definition, buying power will increase. That is, we do not need deflation to re-establish prepandemic levels of buying power. Even with recent growth in real wages, inflation remains elevated, and policymakers have more work to do to lower it while also preserving and building off of the historic labor market gains the U.S. economy has made in this recovery. Bidenomics, with its emphases on capacity-increasing investment, greater competition, and empowering workers should continue to help moving these trends in the right direction.