Valuing the Future: Revision to the Social Discount Rate Means Appropriately Assessing Benefits and Costs

Many decisions, policies, and regulations generate streams of benefits or costs long into the future. For example, the U.S. phaseout of leaded gasoline in the 1970s and 1980s led to short-run transition costs but major long-run health benefits, including by protecting the neurological development of children who would have otherwise been exposed. Economic and regulatory analysis relies on the social discount rate (also referred to simply as the discount rate) to compare costs and benefits that are experienced at different points in time. Using an inappropriately high discount rate would place too little value on the future effects of policy, undervaluing benefits and costs that Americans would experience many decades from now. Conversely, using an inappropriately low discount rate would place too much value on the future effects of a policy.

In practice, for many years the discount rates used by federal agencies have been high relative to more recent, relevant economic data. Consequently, many investments and regulations with long-term benefits related to climate, transportation, health, and other areas have been undervalued. On his first day in office, President Biden issued a Presidential Memorandum directing the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to initiate a process to improve and modernize regulatory review to address this and other issues. As part of that modernization effort, the revised Circular A-4 advised agencies to use a new discount rate in regulatory analysis, with the rate regularly and automatically updated according to a moving average of 10-year Treasury rates. Today, that means the recommended annual discount rate is calculated to be 2 percent, compared to the dual rates of 3 and 7 percent set out in the prior Circular A-4.[1]

In this issue brief, we highlight the economic importance of the new social discount rate established in Circular A-4’s regulatory guidance. Rather than focusing on the interaction between social discounting and climate investments, which have rightly received significant attention in this forum and elsewhere due to the central role of discounting in estimating the social cost of greenhouse gases, we ground the discussion in examples from health and healthcare. In healthcare, investments today—like childhood vaccines—often pay dividends over many decades.

What is a social discount rate?

Mechanically, social discount rates convert future benefits and costs (that are already adjusted for inflation, in the case of dollar-denominated amounts) according to a simple formula. Streams of costs and benefits are discounted by dividing them by (1+r)t, where r is the specified (constant) annual discount rate and t is the number of years in the future that some benefit or cost will be assessed.

The use of discounting reflects the empirical regularity that people tend to value benefits they experience sooner more highly than benefits they experience later. One explanation for such preferences is that individuals (or entire populations) may expect to be better-off in the future, making benefits felt sooner—at a time when they are not as well off—more highly valued on the margin. These characteristics of preferences lead to observable behavior, including in patterns of saving and borrowing reflected in market rates. Another reason to discount is that when regulatory decisions would involve government investment through borrowing, there is a direct conceptual link between discounting as a measure of opportunity cost and the price of borrowing (reflected in interest rates).

Social discounting is separate from inflation adjustment, despite that the analogous use of present value calculations in business economics sometimes lumps these together in a single term. It is best, however, to consider these separately to avoid confusion. Whereas inflation adjustment deflates nominal dollars in the future according to their real purchasing power, social discounting involves a different kind of assessment. It asks, holding purchasing power fixed, what a benefit or cost is worth when it accrues in some future period, relative to what it would be worth if it accrued today. So, if some activity is expected to generate $103 of benefits in one year and inflation is 3 percent, we would first deflate that amount by 3 percent to arrive at $100 in real benefits, and then further discount by the social discount rate, which in the case of a 2 percent discount rate would lead us to value that future benefit at $98 today. In this way, social discounting is layered on top of inflation adjustment, operating on real, inflation-adjusted quantities. Discounting is also important in comparing costs and benefits accruing at different times that are not denominated in dollars (where inflation is irrelevant), such as when phasing-in accommodations for people with disabilities.

What’s the big deal?

Because many public interventions impose costs today for benefits in the future, benefit-cost analysis can be sensitive to the discount rate. For example, about 0.7 percent of U.S. women will develop cervical cancer over their lifetime, which has a five-year mortality rate of about 33 percent. Public health interventions to increase uptake of the HPV vaccine during childhood or adolescence—for example, via public financing to lower or eliminate the out-of-pocket cost of the vaccine—could significantly decrease the population risk of later cervical cancer caused by the virus. Because the median age for cervical cancer diagnosis is 50, the health benefits of the vaccine are substantially separated in time from the initial cost—by 40 years, if the vaccine is administered at the CDC-recommended age of about 10 years old. At the higher 7 percent discount rate used in regulatory analysis prior to the revisions to Circular A-4, the HPV vaccine might not appear to have positive net benefits, even though the vaccine reduces cancer incidence by an astounding 90 percent and does so at a relatively low price.

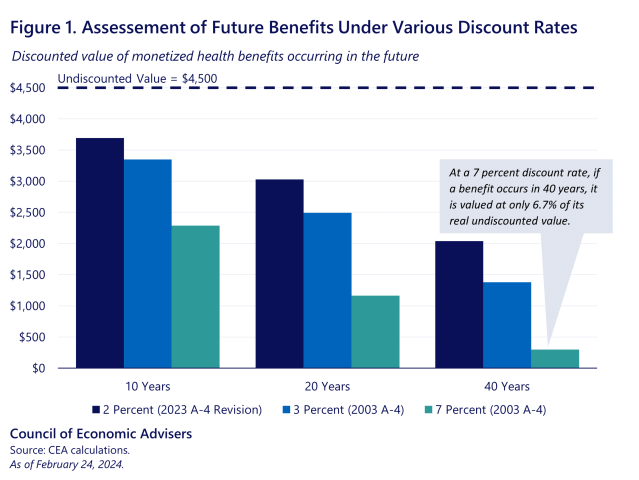

How could that be? A back-of-the-envelope calculation values the expected longevity benefit associated with the vaccine to be at least about $4,500 (when assessed at the time that health benefit is realized).[2] This value averages together the people who would have otherwise developed cancer, for whom the vaccine is extremely valuable ex-post, with everyone else who received the vaccine but would have never developed the cancer anyway (> 99 percent of women). To see how central the choice of discount rate is for valuing costs and benefits that accrue in the future, consider three discount rates applied to this $4,500 benefit: the 2 percent rate recommended in the new Circular A-4 guidance, and the 3 and 7 percent rates in the 2003 version of Circular A-4. Figure 1 shows how the present value of that future benefit is highly sensitive to the choice of the discount rate.

If using a 7 percent discount rate, $4,500 in real benefits are valued at only about $300 when they occur 40 years in the future. Such a high discount rate might lead us to incorrectly conclude that there was very little value in this public health intervention which prevents cancers decades down the road, even though it would cut the incidence of cervical cancer and other HPV-related cancers by over 90 percent! The revision to discounting guidance in Circular A-4 will help to better align our public health priorities by more appropriately valuing benefits accruing to Americans over time.

The long run fiscal impact of Medicaid provision

Consider another example: The expansion of Medicaid to cover more children by raising the income eligibility thresholds. There is excellent research documenting the benefits of childhood Medicaid coverage: better health and healthcare access, but also better educational outcomes, increased adult employment and earnings, reduced chances of later-life disability, and even reduced chances of incarceration. Many of these benefits materialize decades after the children are no longer enrolled in Medicaid.

Because of its benefits and its relatively low cost of providing health care, Medicaid coverage is a good deal. In fact, it is such an outrageously good deal that it looks favorable even if we were to mistakenly ignore most of Medicaid’s benefits in terms of health and life outcomes, and instead pay attention only to what Medicaid meant for the federal government’s finances. That’s because, from the perspective of the federal government, Medicaid largely pays for itself over time.

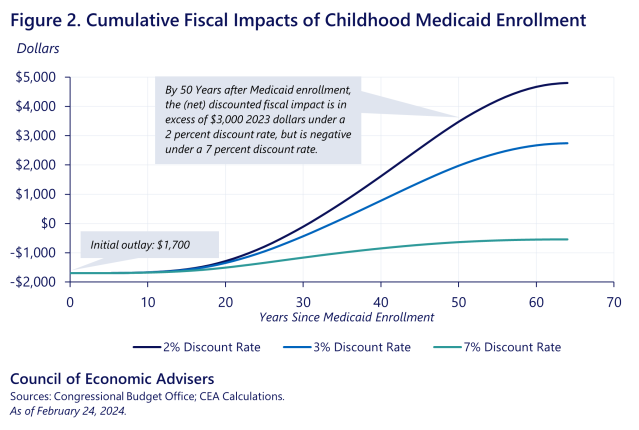

At least, it might pay for itself—depending on what discount rate we apply to future tax receipts.[3] In Figure 2, we re-analyzed data from a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) study (Ash et al., 2023) that tallied the long run fiscal impacts of Medicaid enrollment during childhood. Because children with Medicaid coverage grow up to work more and earn more, they pay more in taxes. They also are less likely to make use of certain government services. The CBO study carefully accounted for these channels based on research evidence about their magnitudes. Figure 2 re-analyzes their results, applying three alternative discount rates to fiscal impacts to illustrate the point that how one values Medicaid depends crucially on how they value the future.

The cost to the federal government of one year of childhood Medicaid coverage is about $1,700. That payment is made up front and not discounted. The greater tax payments associated with that marginal year of coverage start slowly. They are near zero for the first two decades after Medicaid enrollment because it will take time for today’s 10-year-olds to grow up and enter the workforce. But over time, the cumulative fiscal effects of Medicaid enrollment stack up as beneficiaries earn more and pay more back. The narrow view (concerned only with the fiscal effects) leads us to see that under a 2 or 3 percent discount rate, the program more than pays for itself at the federal level. Under a 7 percent rate, it does not.

Better regulation through better economic analysis

To help ensure that regulations serve the public interest without imposing unreasonable costs on society, Federal agencies have long been required to assess the costs and benefits of certain proposed regulations (Hahn 1998; CRS 2022). And in order to consistently value regulations whose costs and benefits manifest over time, such analysis must take a stand on the discount rate. Going forward, the revised Circular A-4 recommends a social discount rate that is operationalized as a 30-year moving average of the rate of return on 10-year Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, similar to the approach taken by Circular A-4 in 2003. In this way, the discount rate is tied to the risk-free rate of increasing future consumption at the cost of current consumption, and updated over time. As of today, that 30-year average—plus a small adjustment for PCE vs CPI inflation—comes to 2.0 percent.

Since the original release of Circular A-4 in 2003, OMB, agencies, and scholars of government regulation have had two decades of insight into the document’s effects on the regulatory process and its limitations in supporting welfare-enhancing rulemaking. The revised Circular A-4 better reflects the frontier of economic theory, methods, and evidence available to help analyze the benefits and costs of regulations and will give Federal agencies the flexibility to incorporate further analytic advances as they are made.

By endorsing a discount rate that is more in line with the expert consensus and moving beyond the out-of-date discount rates used in the past, analysis of regulatory actions and government investments is improving. The adoption of the new 2 percent discount rate in Circular A-4 is a victory for analysis that is informed by the best available economic research. And it is a victory for the American people, ensuring that analysis of government regulations adequately account for benefits that accrue to Americans (or their children) decades in the future.

[1] As explained in Circular A-4 and the accompanying response to public input, this change represents both a lowering of the estimated risk-free discount rate from 3 percent to 2 percent, based on updated Treasury market data, as well as replacing the guidance to use a 7 percent rate in circumstances in which a regulation may displace private capital with guidance to directly account for a regulation’s capital effects and systematic risk (if any).

[2] This back-of-the-envelope exercise is meant for illustration only. Parameters are derived from research that has estimated the vaccine’s benefit in terms of increased longevity. We monetize the probabilistic longevity gains according to a standard life-year valuation. The resulting estimate of the benefit is at least about $4,500 (if provided today).

[3] Why apply a social discount rate to tax receipts, after these have already been inflation adjusted? To account for the opportunity costs of financing these benefits. The OMB-recommended 2 percent rate, linked to the rate of return on 10-year Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, is especially appropriate for analyzing Federal fiscal effects, as the Federal government can directly borrow at TIPS rates.