Labor Market Indicators Are Historically Strong After Adjusting for Population Aging

The U.S. labor market is historically strong, posting elevated and even record measures of labor force participation and employment. By some measures, however, these trends are masked by population aging, which reduces labor supply over time. This post illustrates four facts about the continuing strength of supply and demand after accounting for the impacts of aging.

1. Adjusting for population aging improves comparisons in labor market indicators over time.

The employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) and the labor force participation rate (LFPR) are two closely-watched labor market metrics. EPOP indicates the share of the population (age 16 and older) that is employed in a given month. LFPR is a labor supply metric that quantifies the share of the population (age 16 and older) who either have a job (employed) or are actively looking for one (unemployed). [1]

Over very short periods, such as a few months, these measures primarily only move because of either economic fluctuations or statistical noise in the survey that measures them. Over longer periods, however, changes in the composition of the workforce can weigh on these measures and make them less comparable over time. One major factor at play in the U.S. labor force over recent years is aging.

The U.S. population is getting older on average with each passing decade. Consequently, the share of Americans who are retired is steadily growing. That puts downward pressure on both EPOP and LFPR for reasons unrelated to near-term economic dynamics, and makes these measures harder to interpret as thermometers of economic health.[2]

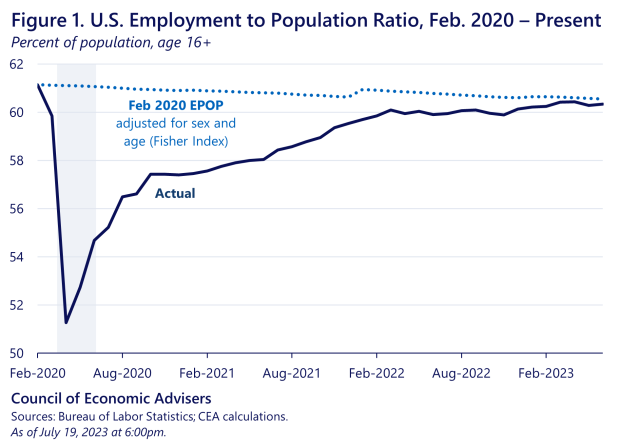

2. Age-adjusted EPOP is nearly back to its prepandemic trend

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the overall EPOP in June 2023 was 60.3 percent, still 0.8 percentage points below its February 2020 level. But how much of this decline is due to population aging versus other economic factors?

Figure 1 isolates the impact of aging on actual EPOP (solid line) by holding each age cohort’s EPOP fixed at its February 2020 level but allowing its population share to evolve in line with actual data (dotted line). The adjusted line is falling at about a quarter of a percentage point per year, which is the rate at which EPOP and LFPR are declining based on aging, rather than other economic effects, such as the business cycle. Figure 1 illustrates that actual EPOP has returned to this age (and gender)-adjusted prepandemic trend.

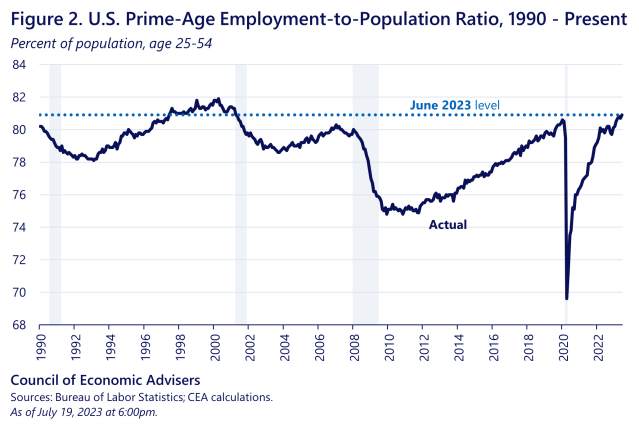

3. Prime-age EPOP is at its highest level since 2001

A common way to adjust labor market data for aging is to look at “prime-age” (age 25-54) individuals, which excludes older workers, who are more likely to be retired, and younger workers, who are more likely to be in school and thus often not working or looking for work. The prime-age EPOP is now above February 2020 levels and is the highest it has been since April 2001. Prime-age men’s EPOP is back to its prepandemic level while prime-age women’s EPOP is currently the highest on record, dating back to 1948. Such a sharp improvement in the prime-age EPOP is an important indicator of the power of persistently tight labor markets, pulling more workers off the sidelines, and providing robust opportunities for job seekers.

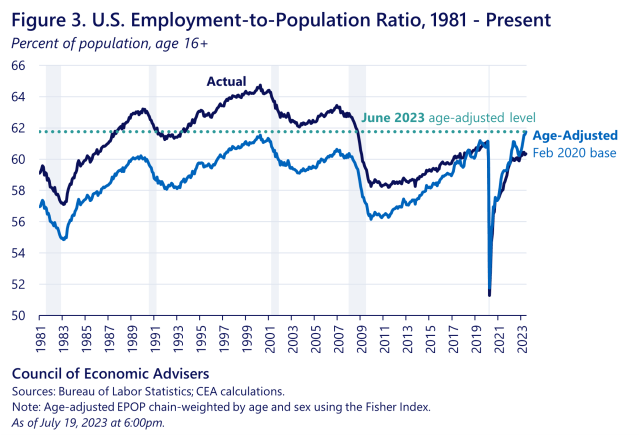

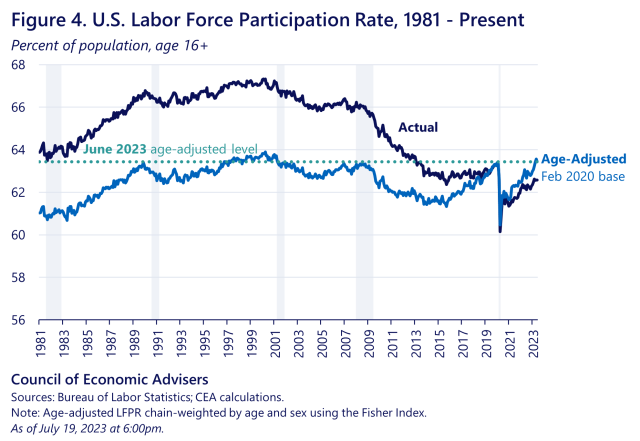

4. Age-adjusted EPOP and LFPR are at the highest levels in decades.

A different way to isolate the effects of aging is to allow each age cohort’s EPOP to change over time while holding constant that cohort’s share of the population using February 2020 as the base period. This is the opposite of the exercise in Figure 1, where each cohort’s EPOP was fixed but its population share allowed to float. The age-adjusted EPOP in June 2023 was the highest since at least 1981 (Figure 3). Since women’s employment rates were lower in the period preceding 1981, the age-adjusted EPOP in June was likely the highest over an even longer historical period. An identical exercise with the LFPR (Figure 4) shows that the age-adjusted participation rate in June 2023 was consistent with rates last seen in 2001. These analyses lead to two important conclusions. First, when looking over extended periods of time, labor market indicators should be age-adjusted to distinguish between secular demographic trends versus other cyclical economic effects. Second, after accounting for demographic shifts in labor supply and demand, the current U.S. labor market is unusually strong from a historical perspective, posting elevated and even record measures of participation and employment.

[1] More precisely, both EPOP and LFPR are measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) as a share of the 16+ civilian noninstitutional population.

[2] Although economic shocks may affect retirements, here we are isolating the longer-term secular decline in labor supply due to aging from other cyclical factors.