New Student Loan Repayment Plan Benefits Borrowers Beyond Lower Monthly Payments

As more than 28 million Federal student loan borrowers restart payments after a multi-year pause, a new income-driven repayment (IDR) plan will help smooth the transition and ensure that borrowers have more breathing room going forward. Income-driven repayment plans enable borrowers to make monthly payments based on their income and family size, with any remaining balance forgiven at the end of the repayment period (typically 20 to 25 years).

The new plan, known as SAVE (Saving on a Valuable Education), substantially reduces monthly payment amounts compared to previous IDR plans, and reduces time to forgiveness to as little as 10 years for borrowers who enter repayment with up to $12,000 in loans (as does the typical community college borrower). It also makes other critical improvements—like the interest benefit explained in this blog— to ensure borrowers who enroll and make timely payments do not experience growing loan balances.

The SAVE plan lowers monthly payments relative to the most similar previous IDR plan (known as REPAYE) in two ways: First, it raises the minimum income level below which monthly payments are set to $0. Second, once fully implemented, SAVE will cut in half the rate that borrowers (with incomes above the minimum threshold) have to pay each month on their undergraduate loans—from 10 percent to 5 percent of discretionary income. More than 1 million low-income borrowers will newly qualify for a $0 monthly payment, and the rest will save at least $1,000 per year compared to previous IDR plans.

IDR enrollment has been shown to reduce the risk of default and increase household liquidity to finance other essentials, including car and home payments. Lower payments alone, however, are not always sufficient to induce borrowers to enroll. Enrollment in previously-available IDR plans has lagged among low-income borrowers in particular, even as they stand to benefit the most from the protections IDR offers against loan delinquency and default. The new SAVE plan lowers barriers that previously stood in the way of higher take-up, by streamlining repayment options, automatically enrolling delinquent borrowers who have given consent to access their tax information, and eliminating the need to manually re-certify income each year.

One of the biggest new benefits to borrowers is how the SAVE plan handles unpaid interest. Under previous IDR plans, some borrowers making their required monthly payments still saw their total loan balances grow, especially in the early years of repayment. When monthly payments amounted to less than interest costs, that unpaid interest would accumulate—and in some cases would become part of the principal, upon which interest could further compound.[1] Research indicates that growing balances create stress and discouragement. Beyond creating anxiety, rising balances can limit access to further credit, and can interfere with successful repayment if borrowers are deterred from IDR enrollment, or if they stop making payments altogether.

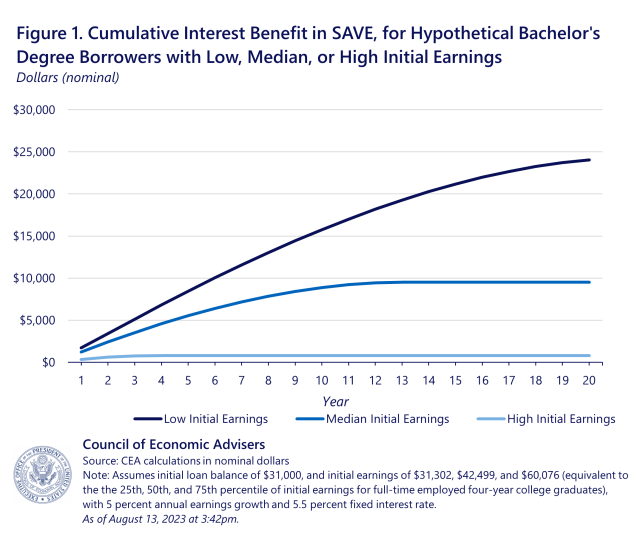

Under SAVE, this will no longer occur: any interest not covered by a borrower’s monthly payment is not charged as long as the borrower makes their minimum required payment in that month. Figure 1 illustrates what this excess interest benefit means for three hypothetical single undergraduate borrowers, who enter repayment with $31,000 in loans and starting salaries equivalent to the 25th, 50th, or 75th percentile of initial earnings for bachelor’s degree graduates.[2] After five years, the median-earning graduate saves over $5,500 in interest that would otherwise be added to their remaining obligation, while the lower-earning graduate saves over $8,400. By the end of the 20-year repayment period, total balances are nearly $10,000 lower for the median-earning graduate, and nearly $25,000 lower for the lower-earning graduate, than they would be without this interest benefit.

To be clear, many borrowers would end up paying the same cumulative amount regardless of this interest benefit, because the SAVE plan (like REPAYE) forgives remaining undergraduate loans after 240 months of payments (or less, for some borrowers). The difference is that with this benefit, the accumulating interest is simply not charged along the way instead of being forgiven at the end. As a result, the interest benefit represents a relatively small fraction (about 11 percent) of the estimated budgetary cost of the SAVE plan. Yet without the interest benefit, borrowers like the lower-earning one modeled in figure 1 could see their balance increase by nearly 78 percent over the intervening years.

The SAVE plan comes at a critical moment as borrowers navigate an unprecedented return to repayment. And student loans, in turn, have been shown to increase college enrollment and completion. By minimizing the risks of unaffordable payments and ballooning debt, the SAVE plan can give future prospective students peace of mind and the confidence to pursue higher education.

[1] The REPAYE plan had a more limited interest benefit, charging only 50 percent of excess interest in general, and no excess interest in the first three years of repayment on subsidized loans. SAVE expands this interest benefit, and a previous rulemaking eliminated all instances of interest capitalization, except where required by statute.

[2] $31,000 is the Federal student loan borrowing limit for dependent undergraduate borrowers. The 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile of initial earnings for full-time employed four-year college graduates are $31,302, $42,499, and $60,076, respectively (measured in 2017, and then adjusted to 2022 dollars). We assume nominal earnings growth of 5 percent annually, based on an analysis of student loan borrower income data from the U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Department of Treasury (see note here). We also assume a 5.5 percent interest rate for loans, which matches the current rate for new undergraduate loans.