This Mother’s Day, More Moms Back at Work, but Care Challenges Remain

As we marked Mother’s Day 2023 over the weekend, we celebrate the vital role mothers play in our economy–by both doing the important work of raising children and contributing to our country’s productivity and economic growth.

Post-pandemic, mothers have reengaged with the labor force, with help from the robust recovery and the American Rescue Plan

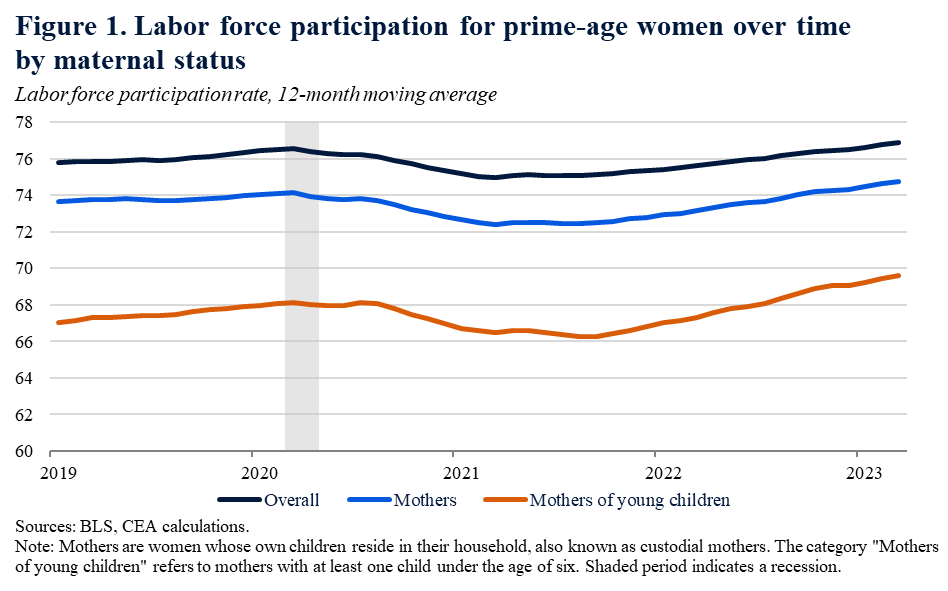

Labor force participation among all prime-age (25–54 years old) women has not only eclipsed its prepandemic level, it is higher than it has been since this data series began in 1948. As displayed in figure 1, mothers’ employment—particularly that of mothers of young children—is also benefitting from the rapid recovery and strong labor market and is above pre-pandemic levels. Following the profound disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic, many mothers who left the labor force have reengaged at high rates, with labor force participation among mothers of young children at 70 percent as of March 2023, and that of mothers of any children under 18 years old at 75 percent.

The rapid reengagement of mothers in the labor force has occurred despite challenges. The childcare workforce undergirds the American workforce, and employment in childcare was disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, falling more than 35 percent between February 2020 and April 2020. The recovery in childcare employment remains behind the rest of the economic recovery. As laid out in the CEA’s analysis included in the Economic Report of the President (Chapter 4, box 4-2), the American Rescue Plan, signed into law in March 2021, potentially played an important role in the recovery in maternal employment. It included $39 billion in new childcare funding to support childcare providers in retaining staff and remaining open through the pandemic-induced economic downturn.

Working mothers often scale back in the workplace to balance caregiving responsibilities

When participating in the labor force, women, and particularly mothers, are much more likely than other workers to be employed part-time. CEA analysis of data from the Current Population Survey shows that among employed mothers of children under age six, 27 percent are working part-time compared to 11 percent of employed fathers of young children and 21 percent of all employed women. Survey evidence also suggests that the pandemic led families to make shifts to balance work and caregiving responsibilities. Some of these adjustments may be unsustainable and may compromise women’s labor force attachment over the long term.

Initially, the pandemic led to changes in employment patterns for those with caregiving responsibilities, with mothers more often taking leave from their employment due to pandemic closures than fathers or women with no school-age children. During the pandemic, prime-age women were more likely than men to work from home; among those looking for work, prime-age women were nearly twice as likely as prime-age men to indicate that their search was not urgent because of childcare obligations, and employed, prime-age women also more commonly reported that they were searching for a new job because they wanted a remote job. Survey data from October 2020 indicates working mothers were more likely than working fathers to report that they could not give 100 percent at work, that they needed to reduce their work hours, and that they turned down an important assignment or a promotion because they were balancing work and parenting responsibilities.

These pandemic effects on working families have lingered. Through February 2022, parents, and particularly working mothers, continued to report difficulty handling childcare responsibilities. This burden is on top of longstanding divides in who does care work inside the home: 2021 data from the American Time Use Survey indicates that mothers of children under age six spend an average of 2.8 hours per day on childcare, over 70 percent more time than fathers report.

Supporting caregivers could boost their labor supply

Since the mid-20th century, the rise in women’s participation in the labor market has been critical to our Nation’s economic prosperity. CEA calculations indicate that the U.S. economy was almost 10 percent larger in 2019 than it would have been without the increase in women’s employment and hours worked from 1970 to 2019.[1]

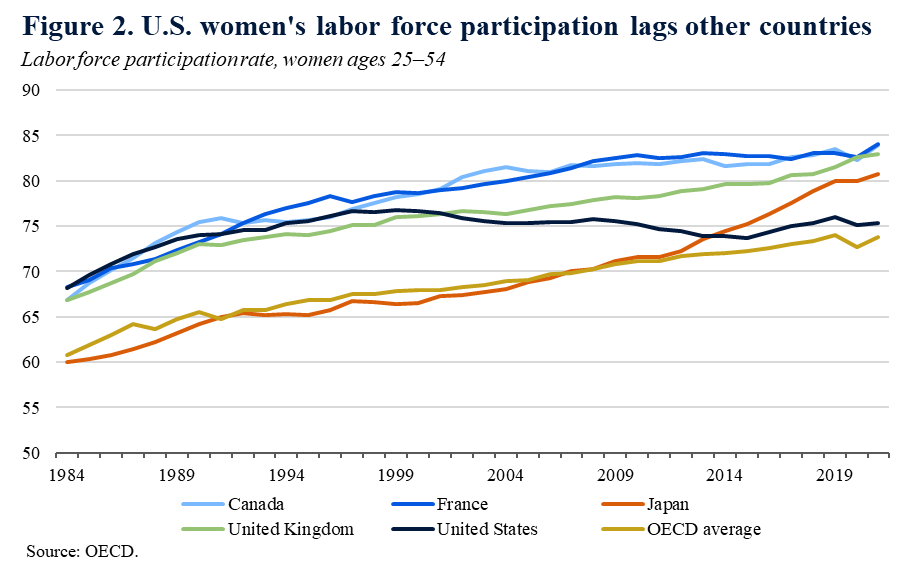

In recent decades, however, labor force participation among prime-age women in the United States has stagnated and experienced periods of declines, falling behind peer countries (figure 2). While the pandemic laid bare challenges for parents and caregivers in balancing care and work responsibilities, particularly in 2020, the existence of untapped labor supply among prime-age women predates the pandemic. The post-pandemic recovery in prime-age women’s labor force participation is strong, including April 2023’s record high labor force participation rate for prime-age women, but the United States still lags behind our economic competitors.

One analysis suggests that the United States’ relative lack of family friendly policies, including limited funding for and availability of childcare, partly accounts for U.S. women’s relatively low labor force participation, and lack of growth in the early 2000s, as compared to other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. This study finds that the policy environment explains nearly one-third of the gap in U.S. women’s labor force participation relative to other countries. While this is just one study, a larger body of evidence finds, as common sense would suggest, that mothers’ employment is responsive to the availability and affordability of early care and education for their young children.

The Biden-Harris Administration has emphasized policies that support parents and caregivers, with the successful passage of the bipartisan FY23 funding bill—which included more funding for early care and education and new protections for pregnant, postpartum, and nursing workers through the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act and the PUMP for Nursing Mothers Act—and the President’s recent executive order which directs agencies to, “make all efforts to improve jobs and support for caregivers, increase access to affordable care for families, and provide more care options for families.” Unlocking the full potential of mothers’ labor supply while also supporting their critical role in raising children requires investments in working families, like those called for in the President’s FY24 budget proposal, including paid family and medical leave, paid sick days, affordable, high-quality early care and education and home care, and expansions of the Child Tax Credit. Ensuring that mothers and mothers-to-be can fully engage in the workforce as they choose is a step forward for families, working parents, the health and well-being of children, and our collective economic prosperity.

[1] Using methodology similar to the 2015 Economic Report of the President, this estimate is based on actual GDP growth compared to hypothetical GDP growth if women’s labor force participation and average hours of work had remained at 1970 levels.