Seven Facts About the Economics of Child Care

Those who care for children, the elderly, and people with disabilities are vital for the healthy functioning of our economy. Access to affordable, high-quality care allows individuals to enter the labor force, reduce absenteeism at work, and retain more of their income to spend on basic necessities like food and housing.

The Biden-Harris Administration has demonstrated its commitment to supporting affordable care through direct investments such as the American Rescue Plan, the CHIPS and Science Act, and each of its annual Budgets. On the one-year anniversary of the Biden-Harris Administration’s Executive Order on Increasing Access to High-Quality Care and Supporting Caregivers, this blog focuses on child care specifically, highlighting seven reasons the economics of child care necessitate policy interventions like those enacted and proposed by the Biden-Harris administration to make high-quality, affordable care available to more working families.

1. The provision of child care is currently at an inefficiently low level. While the benefits of high-quality childcare extend to the entire society, the financial burden is primarily borne by individual families. This scenario is an example of what economists call positive externalities: longer-term benefits to society beyond what’s captured in today’s costs to families. It thus presents a textbook case for public subsidies for child care provision because relying on families alone to foot the bill will lead to the under-provision of care. First, access to high-quality care enhances academic outcomes for the children who receive it, but also those of their future classmates (Neidell and Waldfogel, 2010). Second, reductions in criminality associated with high-quality child care have large societal cost-savings (Anders et al., 2023). Third, a large literature links increased maternal labor supply to access to childcare (see Morrissey, 2017 for an overview). This not only improves outcomes for mothers affected, but also enlarges the labor pool, benefiting local businesses and the economy broadly. In fact, indicative of benefits for businesses, private companies are increasingly providing child care benefits to their workers as a strategy to retain talent and reduce absenteeism at work.

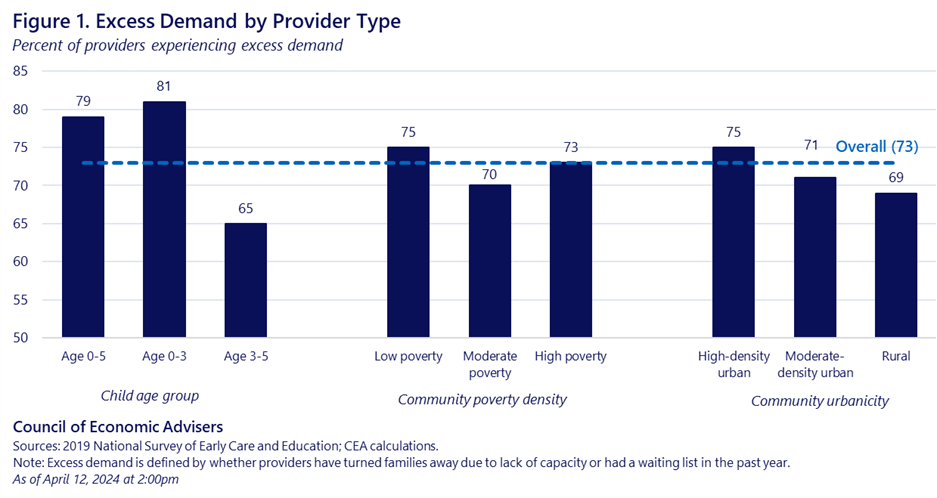

2. The child care business model has been historically unsustainable. The child care market is a decentralized patchwork of providers caring for children in homes, centers, and schools. While this varied landscape helps to provide families the flexibility to choose the early care and education (ECE) options that best meet their needs, challenges in the market lead to a persistent gap between the cost of providing high-quality care and prices that families can afford. On the supply side, businesses struggle to invest in quality improvements such as increased compensation for staff or lower child-to-educator ratios while charging rates that families can afford. On the demand side, families face liquidity constraints given that child care costs are more likely to come at a time when parents are in the early and relatively unstable years of their careers. This mismatch leads to underprovided high-quality child care relative to demand from families (Figure 1): in 2019, over three-quarters of households that searched for care for their young children in the same year had difficulty finding care that met their needs.

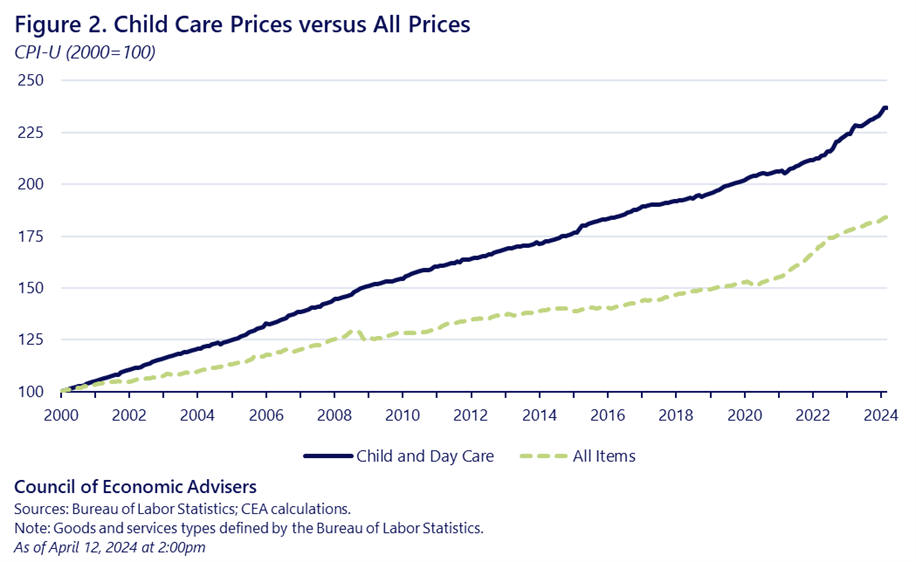

3. Child care costs have been growing rapidly; wages for child care workers remain low. Child care prices rose 210 percent—nearly three times as fast as the overall price index (74 percent)—from 1990 to 2019. While child care worker pay has seen recent increases, the median pay for a child care worker in 2022 was still under $30,000 per year. Persistently low wage prospects make attracting and retaining workers difficult, and issues with recruitment and retention can limit the supply of high-quality care, as discussed above. Public subsidies on the demand and supply sides of the market—such as those enacted through the American Rescue Plan and highlighted in fact 7 of this blog—can target issues of cost and pay, allowing providers to invest in often costly, high-quality improvements such as worker compensation without raising prices faced by consumers.

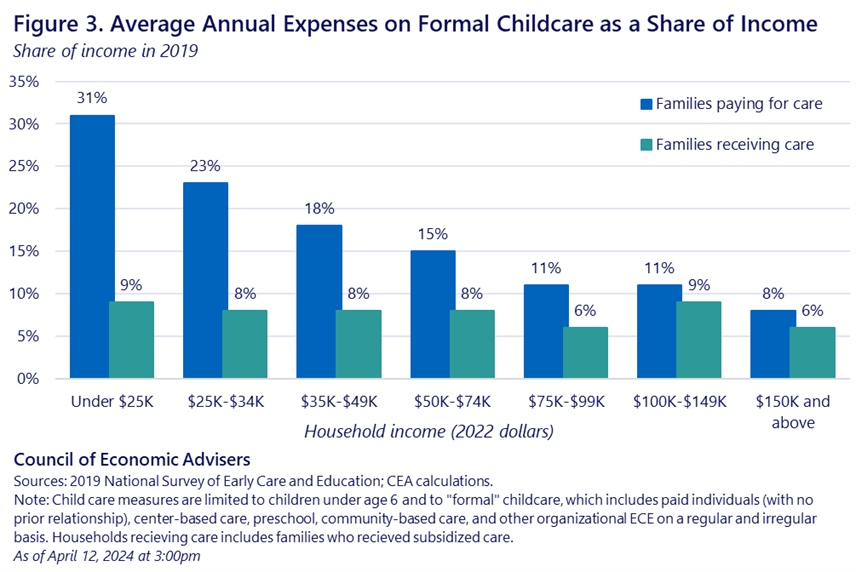

4. Low-income families face the greatest cost burdens. Families are often burdened with the cost of child care when they can least afford it: early in parents’ careers when incomes are lowest and they are saddled with other major expenses like mortgages and student loans. This makes borrowing against future savings to pay for child care difficult, limiting families’ ability to smooth their consumption. Costs are especially salient for low-income families, who tend to spend a greater share of their take-home income on necessities. Another stressor on those incomes—such as child care—makes it difficult for families to afford necessities like food and shelter. Due to cost and other access issues, low-income households also have the hardest time finding care: over 70 percent of children in households with income between $20,001 and $40,000 that searched for child care reported some difficulty finding it in 2019. Importantly, while many lower-income households would likely qualify for subsidized care, capacity constraints often mean that participation among eligible families is low. Figure 3 shows the potential cost savings among families that do receive these benefits (comparing the green and blue bars); unfortunately, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that in 2019, only one in six children eligible for care benefits received them.

5. Investments in quality childcare produce enormous returns for children. The long-run benefits associated with high-quality early educational experiences means that the return on these types of investments are often high: estimates of the long-run benefits of high-quality child care find a $7 to $12 return on every $1 invested in high-quality programs (Heckman et al. 2010). Investments in quality care support children’s healthy development and early learning from birth, which lead to longer-term benefits for individuals and families that can spill over to their communities and the economy more broadly. The long-term, positive effects of child care programs on outcomes like educational attainment, employment, and earnings have been thoroughly and rigorously demonstrated in the research literature (Heckman et al. 2010; Duncan and Magnuson 2013; Gray-Lobe, Pathak, and Walters 2023).

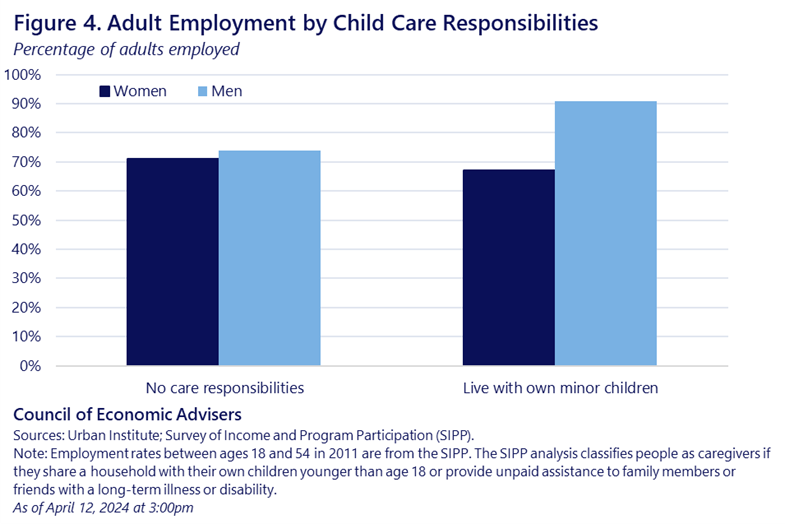

6. Access to quality, affordable childcare allows parents to remain in the workforce. Despite record levels of female labor force participation in 2023, data suggest that working mothers tend to take on a disproportionate share of caregiving responsibilities, scaling back hours in the workplace or leaving the workforce altogether for extended periods of time. Employment changes like these can negatively impact a woman’s lifetime earnings and career trajectory. CEA analysis of Current Population Survey data found that, among employed mothers of children under age six, 27 percent are working part-time compared to 11 percent of employed fathers of young children and 21 percent of all employed women. On the anniversary of the Equal Pay Act, the CEA published a blog highlighting the challenges remaining for women in the labor market and the role that care burdens play in gender-based wage gaps across the income distribution.

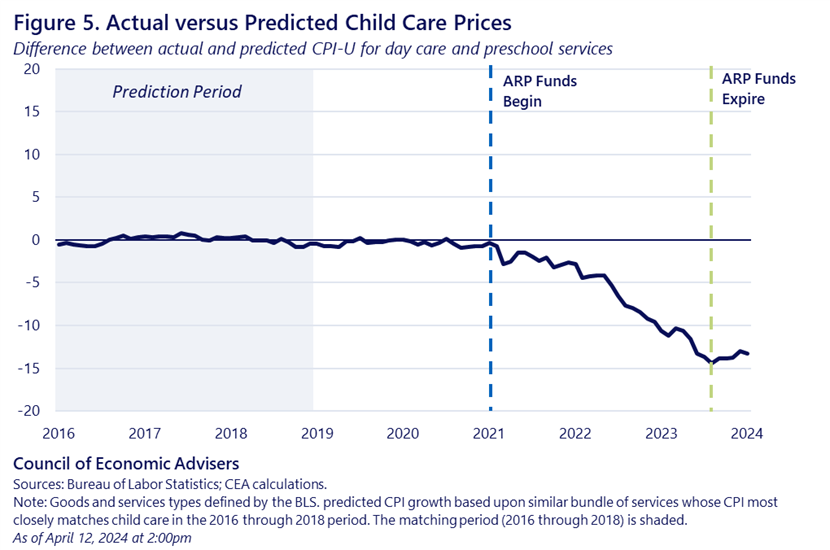

7. Federal funding through the American Rescue Plan has played an important role in stabilizing the child care industry. Finally, recent work from the CEA has highlighted how Biden-Harris Administration action has benefitted paid and unpaid caregivers: improving the economic prospects of workers—as reflected in wages and employment—and allowing individuals with care-giving responsibilities to participate more equally and fully in the labor market. This funding succeeded in slowing cost growth for families over a period when overall inflation was accelerating, stabilizing employment and increasing wages for child care workers—a group disproportionately comprised of women, and whose wages are historically close to minimum wages— and increasing maternal labor force participation. In short, these funds were key to stabilizing the industry during an uncertain time, and the analysis highlights the power of federal funding to expand access to care for families while improving the wages and employment prospects of care workers.

The Administration has continued to uplift the importance of care and supporting care workers through the Executive Action, rulemaking, and Budget processes. This Care Workers Recognition month, we can all thank a caregiver in our life, acknowledging how their work transcends the individual or community by generating benefits that better the economy for everyone.